"I Don’t Know if a Duck is Going to Swallow me Whole." The Tim Schafer Interview.

Tim's history, career – and the ups and downs of game development and crowdfunding.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Going back to Tim's early career. I ask how he made the transition from college to games programmer

"I had an Atari 800 and I was trying to make games, though not very well. I learned 6502, but I was not super good at it. I studied computer science in college. I picked it mostly because I knew how to program, so I figured I could handle it. But as I was going through college, I became more interested in creative writing and started taking creative writing classes. I wanted to be like Kurt Vonnegut, you know, writing short stories. I would read stories about his life and he worked at General Electric as an engineer during the day. Then at night he would write short stories. He got his first check for $300 and I was like, "I want $300!" So I’ll get a job programming databases because those are so plentiful that I didn’t even have to think about it. The only jobs you saw were database-programming jobs."

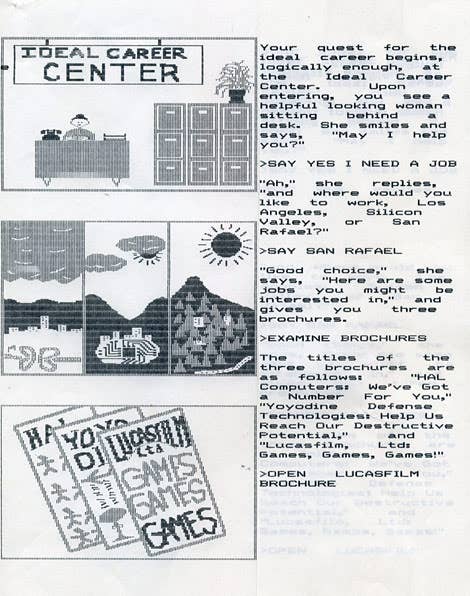

"I had done some internships writing billing databases for people and stuff like that. I was on a job hunt that involved a second interview on The Peninsula with this nice company where they were making databases for police departments and fire departments to track service calls and weed abatement. The fire department wanted to know what vacant lots had weeds in them. So I wrote a database for that. Then I had put in some token databases for Atari and Hewlett Packard. I wanted a job with computers. I got turned down from all of those. I still have their rejection letters for all of those. Then I saw the job listing at the Career Service Center at Berkeley where I went to school. They wanted programmers that could write dialog at Lucasfilm Games (before it became LucasArts). I was like, "What!? This is amazing!" I loved Lucasfilm, not because of Star Wars, but because of the Atari stuff they did: Rescue on Fractalus, The Eidolon, Koronis Rift, and mostly Ballblazer. So I was really excited."

"That’s the interview I famously blew because David Fox asked me what other games had I played. I responded, "I love Ballblaster the best." He said, "Ballblaster, eh? I thought it was called that in the pirated version." I had gotten that on a disk from a friend of a friend of someone who worked at Atari and would make this disk of 16 games. And that’s where I had played it. I thought I had blown it. He said, "Send in your resume with a cover letter describing your ideal job." So I sent in a cover letter that had a little text adventure with pictures of me trying to find my ideal job. It had dumb pictures that I had drawn. That got their attention and that’s why I got the job."

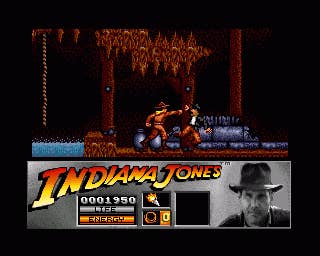

"I was hired as a scummlet, which is an assistant designer/programmer. But they called it scummlets, which is the lowest rung on the totem pole. Guys like Ron Gilbert and Hal Bartlett, as well Hugh Howells and Brian Moriarty were there and they were directors and they wanted a bunch of scummlets to come implement all of their ideas. When I first got there, they didn’t have any scummlet work for me yet, and so Dave Grossman (who I would later make Monkey Island with), and two other scummlets were put onto testing the Indiana Jones action game. There was an adventure game – Indy 3 – and an action game that was widely derided and not so popular."

"It was funny because I didn’t know anything about game development, but I played the game and ended up walking off a bridge and crashing it. I went into the room with all these guys and was like, "Hey, if you walk off the bridge it crashes." They all just looked at me like they wanted to kill me. That was my first experience with QA. And now I know that look because I give it all the time. No one touches the game, and then someone finds a crash. So I definitely know what it’s like to be a tester. So I tested that game. I tested Loom a little bit, because that was right when it was about done. Then, they started SCUMM University where they had Ron teaching the four of us all about SCUMM. They would have a lesson in the morning. We would mess around during the daytime trying to implement all of these things we just learned like how to add a room to a game, how to put lock boxes on the floor, how to make the character walk around, how to make objects flip and go through animation states. It was really so much super fun. It was a super fun period."

"I was working at Skywalker Ranch; the last movie they had made was Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Lucas was still a really magical place. Everything still had the glow of early Star Wars all over it. The ranch is beautiful. It’s this Craftsman-style building next to a Victorian building next to an Art Deco building, surrounded by vineyards. There was fog rolling over the vineyard. Deer walked by and you were drinking gourmet coffee there. Anyway, it was a great job and we learned SCUMM."

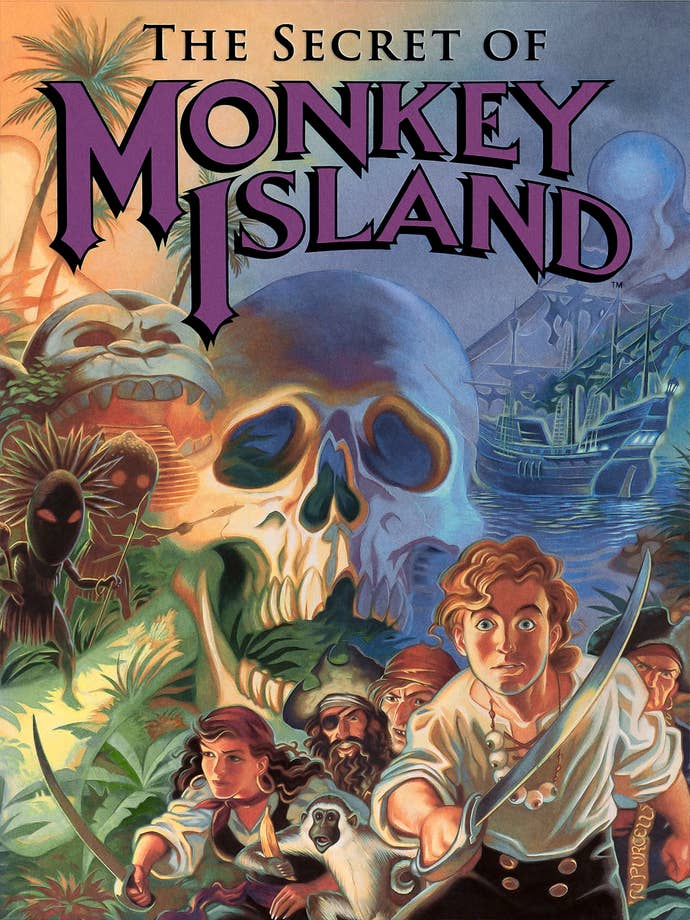

"Then one day Ron came up and showed Dave and I his secret document for this new comedy pirate game that he wanted to do. It was exciting. So we started talking to him about it. The character was just called Guy at the time. We started working on what became, "The Secret of Monkey Island". That was also really fun."

How did you influence "Secret of Monkey Island"? What was your contribution?

"There’s a myth that goes around about how it wasn’t a comedy until Dave and I came along, but that’s not true. It was always going to be a comedy. The thing that I think gets misunderstood is that I thought we were writing temporary dialogue for it and so we were just writing really silly, stupid dialogue. Then Ron was like, "That’s the dialogue we’re going to use." I was like, "What!?" It was great. It kept me from being too nervous about what I was writing. It was a good exercise to pretend you’re writing temporary dialogue. Come back and fix it later, if you have time, but it’s fine."

"Ron wasn’t as controlling with the dialogue as I am. I like to write everything for the games. Ron said, "Let us write our own sections." So, I wrote certain sections: Stan the used ship salesman, I was writing the puzzle where you try to go and buy a ship from him. I made it way more complicated than it probably had to be. It was the most in-depth dialogue puzzle tree ever written, probably. Then, the shopkeeper. Dave would write his stuff. He would focus on Herman Toothrot and the men of low moral fiber. We had all of the little set pieces that we would work on. Ron would work mostly on the ghost ship, the puzzles on the ghost ship, and all the LeChuck cut scenes. So we were all working together. We would all check out each other’s stuff in mid-afternoon. Some of the first play testing we would do is, "Let me see your dialogue," and Ron would play and we would watch to see if he would laugh or not. Then we would go change stuff furiously. Dave got a laugh, so I’d want to get a bigger laugh than that. Then we would encourage each other. There was no Internet back then, so we were just trying to use the people in the room with what we wrote. It probably led to a certain style of humor."

How iterative was the process? If you’re going back fixing dialogue and trying to get a bigger laugh, was the dialogue more of an evolutionary process?

"We always said it took two days to write a dialogue tree, but it probably took a week. We would have playtest sessions and we would watch people play it and see what they would laugh at or what they didn’t laugh at. Lucas had this thing called the "Pizza Orgy" where they would bring in all of their friends and family and they would stay all night and everyone would just play the game and eat pizza. And not have sex, hopefully. It was an orgy of gameplay and pizza eating. Then they would get everyone together to talk about the game. That’s something that we keep going at Double Fine. We have these mandatory hours of where we force the whole team to play the game, and then you get everyone to talk about it."

When you were writing the dialogue, you hadn’t really written anything like that before?

"I had written a short story. I won the Engineer’s Short Story Contest for a very embarrassing short story that will never see the light of day. So I was writing, but I’d never written scenes with people like that. I had written a few little stories in Creative Writing class."

What influenced you?

"Right around the time we were starting Monkey Island, The Simpsons premiered. The very first Simpsons came out. We were like, "this is a phenomenon! This is the funniest thing that has ever existed in the world!" So we were all watching that together and I think that had a very big impact on what we were doing. Before then, my writing influences were Kurt Vonnegut and I think there’s a lot of Monty Python in Monkey Island. Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy probably was a big influence. Dave read a lot of P.G. Wodehouse's Jeeves books."

"We were mostly writing in a sarcastic style. I remember being told at one point after Day of the Tentacle, "We need to sell more of these adventure games. The problem is you guys are kind of funny the way David Letterman is funny, but you need to be more funny the way The Simpsons is funny." I think they just meant, there are two kinds of sarcastic senses of humor, but one is more popular than the other one. The Simpsons is more mainstream and David Letterman is more niche. That was the early days of David Letterman when he was more edgy and niche-y."

"Where did those jokes come from? Sometimes, they’re personal. I was writing the Cannibal dialogue and I was like, "I don’t know what to do. What should I make them like?" Ron was like, "maybe they’re cannibals, but they’re really health-conscious cannibals." My family was just going through this thing where they were all on low-fat diets, so I just reused family dialogue about red meat and stuff and put that all in there. So, it comes from all different places, for sure."

So, moving on to Full Throttle. That was your first full game that you originated?

"Yeah, we had done Day of the Tentacle with Dave and that was influenced a lot by Chuck Jones cartoons. We even brought Chuck Jones in to look at it. We were hoping he would make a blurb for the box, but the only thing he said was, "It looks good, but why am I here?" which is not a good blurb. We should maybe put that on the remake!"

"We had done that, and then Full Throttle was the first game that I led and designed by myself. It was the first one where I was starting to study screenwriting. You can see that influence in it, I think. There were a lot of farce and jokes and stuff like that. I could tell that I read this Sid Field screenplay book and I was thinking about act structure. He was really influenced by Yojimbo, Toshiro Mifune, and the Akira Kurosawa film. Have you ever seen that movie? This really stoic hero who just doesn’t really talk that much and just scratches his neck once in a while and that’s it. Then the Road Warrior was obviously a huge influence on Full Throttle. I think Road Warrior was really influenced by Yojimbo. Just trying to do a character like that. So I was trying to really craft a character and a story arc in that one. It was the first time trying to have things from the ending tie in with the beginning, like I was in film school or something. It was also the first time we had full-screen animation, but because of that the game was much shorter than Day of Tentacle, because we put all of this work into the cinematics. So people complained that it was too short. That was my first experience with Internet hate. But luckily, I didn’t have a CompuServe account, so I didn’t have to read it. Someone would just tell me about it: "CompuServe says some people are mad.""

"One of our producers said, "I liked it, it was a pleasant way to spend an afternoon." I was like, "You jerk." But, I think then after Prince of Persia came out, eight hours is fine. People were really mad about Prince of Persia. Nowadays, a lot of games are eight hours. I guess people just think about how much money they spent on it. $15 leads to probably a six-hour game sometimes. Like Limbo. Everyone talked about that being short, but no one seemed to be complaining about it really. It was awesome. It was an awesome experience. It was well-crafted and no one seemed to mind."

What do you think is more important. Is it the story, puzzles, or gameplay? I know they’re all really important, ultimately, but how do you prioritize them?

"I feel like they’re all sort of the same thing. Ben Throttle’s character influences how he solves a puzzle, and how he solves a puzzle tells the story, and solving the stories is the gameplay. So I guess I always think that they’re this one holistic thing. I feel like everyone has their own priorities for games. I think there’s this illusion that there’s a fight between gameplay and graphics. That used to be the big thing in the ’80s. Everyone was like, "Gameplay!" But I feel like gameplay, graphics, audio, and story are all tools in the toolbox. The ultimate goal for me is to just transport somebody to a fantasy world and keep them there for as long as possible… because that’s what I love. To just go to fantasy worlds and be immersed in there and not want to come out; to miss it when I’m not there. So I feel like gameplay can hook you into a world and make your brain feel engaged, but you know, a story can too. If you just love the characters, you can feel engaged too. The atmosphere. Sometimes a game’s atmosphere just makes you want to hang out in there forever. If it’s missing a key element of that, and it’s something you like, then you’re not going to feel immersed. If the gameplay is bad, you’re not going to want to stay there for very long. So they all really have to be firing."

Do you think there is a bit too much emphasis on graphics and technology these days?

"Maybe it’s just me, but this generation, but I don’t see a whole new world opening up. The graphics are not so much better that I’m seeing things I never saw before. They’re just nicer and they’re running at 60 frames a second. But if you’re on the PS4 and you’re playing Bloodborne, you can see this whole city behind you and it’s amazing, or I can play Hohokum and it looks beautiful and the art direction is really more important than the number of polygons being shown. So to make an argument that one is better than the other is just ridiculous. I think they’re obviously going for different things and you can enjoy them both just as much."

Do you think that gaming is becoming more of an art form in that sense? What you’re really describing is that the palette is beginning to max out. In that sense, it’s about stylistic interpretation and creativity differentiating games?

"I feel like it’s always been that way. It’s always been an art form to me. An example I always use is that we could have made Tetris on a pretty good character-based terminal on a Unix machine; in fact, I think it was written for that. Use certain ASCII characters; you could make a pretty good ASCII version of Tetris, right? It didn’t need any sort of graphics; any sort of fancy anything. Why wasn’t Tetris a thing until Tetris was a thing wasn’t technology, it was just that no one had had that idea yet. So ideas hold us back, not technology. I feel like there are games we could make right now with existing technology that no one has thought of. They could be the next big, amazing games. New technology comes out and it definitely opens doors and allows people to have amazing experiences. Maybe if we hit that point where we’re not blowing everyone away with technology every generation, people will be like, the only thing that will make my game stand out is the ideas and the artistry of it. That’s the only way to really blow them away. That’s a good thing, I think."

Which games have blown you away because of their artistic direction, rather than the technology?

"I guess Hohokum was my example of that where it was really a beautiful calm and meditative game play. Swapper had its own style. For me, it’s just as long as it just looks like no other game. Playing Never Alone, that was really beautiful and a whole different take on things. I would put Broken Age in there. [laughs] It’s not the technology that is being used to impress people, but that someone took existing technology and made creative decisions that made new things you hadn’t seen before."

I have a sort of odd question: In Star Wars: Shadows of the Empire, you're credited with "Never Actively Tried to Sabotage the Project". What was that all about?

"I feel like that was just more an example of how the old LucasArts was, where we were all working together and all working on really disparate things. Like Shadows of the Empire, Dark Forces, and TIE Fighter being made alongside Grim Fandango, Full Throttle, and Sam and Max. You know that was such a great collection of different people on working on different stuff, but still being friends and supporting each other. I was friends with the Star Wars: Shadow of the Empire team. I was making a joke and demanding a credit because they were making it. I was like, "What’s my credit going to be in this game?" They were like, "You didn’t do anything in this game." And I was like, "Well I never actually tried to sabotage it, that’s something, right?" So I think that was their nod to my begrudging demand that I be included in the credits.

Did you actually help out on the game at all?

"No, absolutely not. The only game I did sabotage was Full Throttle 2"

What happened with that?

"That’s what made me start my own company, in some ways. Not that version of Full Throttle 2, but an earlier version. There was an iteration no one saw where I was like, "What are Jonathan and Larry working on after Monkey 3?" I think someone was like, "Well, I think they’re working on a Full Throttle sequel." And I responded, "My Full Throttle? My game? The game that I came up with? They’re working on a sequel to that? No one’s talked to me about that at all." Management just asked them to work on it because I was busy with something else, and they were like, "Let’s have them work on it." In management’s mind, that was just Lucas’ property. In my mind, that was my game. I own that! Ben was named Ben because I was almost named Ben when I was a kid. This is my game! It was just such a shock to me. Then I realized, well, I guess that’s fair. I got paid for my time to be here. George Lucas paid for me to make that idea and now he owns it. That’s fair. So I’m not really mad about that, but never again. I’m going to start my company and we are going to own everything we make. So far, we have. We have owned every IP; we just got back Iron Brigade. Sometimes we lose them, but we get them back. That’s always been a very important founding thing for the company. I feel creative people should own the stuff they make. I don’t think just because someone else helped you fund it, they funded it and got all the money from it and so you should be able to keep your ideas. I guess that’s just the way I feel about ideas. I feel like I came from this model at LucasArts where you had an idea and you were the one that made that game. A lot of the companies, someone has an idea and you hand it off to a producer and it gets made. I just feel it leads to a more disconnected, less passionate personal artistic product in the end."

What worried you about Full Throttle 2? That it wasn’t going to be you making it, or that someone was going to mess up the idea?

"I just felt really weird that someone else was going to decide what would happen to Ben…. I just felt really controlling. Like, they could kill Ben or they could kill Maureen, but those were my people. They could make it so that two characters hated each other who should never hate each other. Looking at what Ron went through with Monkey Island, he felt a lot of ownership of that, but he left. And then they made Monkey 3, which was a really good game, but I think things happened that aren’t what Ron would have done. Elaine and Guy got married. That never would have happened if Ron were doing it. There’s a reason they broke up at the beginning of Monkey 2, and they have this romance, but obviously Elaine could do better than Guy. You feel ownership over something you don’t own. The idea of creative ownership versus legal ownership is a weird thing."

Up next: Grim Fandango, the Double Fine years, and the ups and downs of crowdfunding and game development.