Gaming Auteurs: Akitoshi Kawazu

No one in the world makes RPGs quite like those of Final Fantasy's quirkiest co-designer... for better, and for worse.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Games have so many moving parts, it's often impossible for one person's singular vision to shine through the many layers of content. But sometimes, we get lucky.

When people think of the auteur concept as it relates to video games, they usually call to mind directors with an obsession for film and narrative: David Cage, Hidetaka Suehiro, Goichi Suda, Rockstar's Houser brothers, maybe Ken Levine. Video games aren't simply glorified movies, though; their interactive element makes them unique, and designers can leave their mark on the medium with systems and mechanics just as meaningfully as they can with immersive narrative.

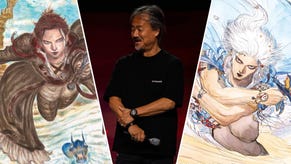

Bob recently wrote about the driving inspiration behind the work of Hideki Kamiya's work — his obsession with the nuts-and-bolts of his action games, and his careful attention to player interaction and feedback. Being more of an RPG fan myself, though, the design auteur whose work most speaks to me is Square Enix's Akitoshi Kawazu. Despite his work's unique qualities deriving almost entirely from its mechanical features, Kawazu's oeuvre couldn't be further from Kamiya's.

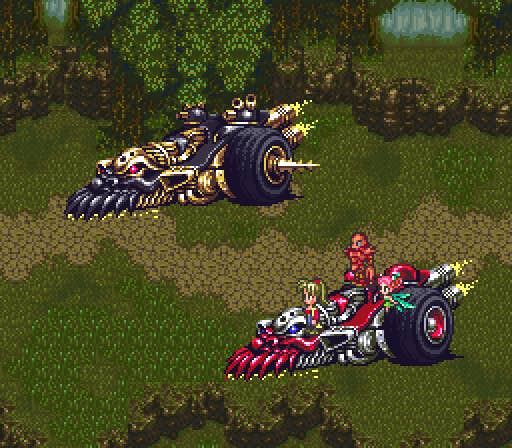

Some history, first. Along with fellow Famicom Final Fantasy collaborator Hiroyuki Itou, Kawazu is the last of Square Enix's true old guard, having joined Square back in the mid '80s and first making a name for himself by directing Rad Racer and co-designing the very first Final Fantasy — two of the first three Square games to make it to the U.S. The success of the latter game and its crucial role in keeping the struggling company from hitting rock-bottom gave its team of creators considerable influence within Square, which translated to the freedom to create games as they saw fit.

That newfound liberty saw many different expressions. Final Fantasy lead designer Hironobu Sakaguchi continued his efforts to make role-playing games less arcane, more accessible, and more exciting. Meanwhile, Koichi Ishii and Hiromichi Tanaka drifted in a complementary direction, adding RPG depth to action games with the Mana series. Kawazu, however, went off on his own tangent; he designed RPGs, but they were RPGs like no one else made.

Fundamentally, Kawazu's key interest lies has always been in taking video game RPGs back to their tabletop roots. Whereas the general direction of Japanese RPG design is to push more toward the feeling of visual novels or anime supplemented by stats-based systems, Kawazu's games treat narrative more as an incidental consideration. Ultimately, his works serve as sandboxes in which players can experiment with systems that could best be described as "idiosyncratic."

"When I design games, I analyze elements of board games and how they work," Kawazu once told me. "It is at the foundation of a lot of the games I make."

His peers clearly recognized or intuited this fascination from the beginning and assigned him to appropriate tasks — and he rose to the occasion. On the original Final Fantasy, he says, he "was mainly in charge of the battle system and battle sequences. For that, I tried to make it as close to Dungeons & Dragons as possible. That was my goal.

"There are certain precepts when it comes to a Dungeons & Dragons type of environment, a western role-playing experience. Like 'zombies are weak against fire,' or 'monsters made of fire are weak against ice.' If you think about it a little, they all make sense, and these are all things that D&D already sets up. Certain things are weak against certain other things and strong against yet other things. They all have these relationships. Up until that point, Japanese RPGs were ignoring all of that. They didn't incorporate those elements."

Kawazu's influence in the original Final Fantasy played a key role in shaping the future of console RPGs. Other Famicom RPGs of the era took their cues from Dragon Quest, where spells had no elemental traits — magic could hurt, heal, or stun, but the idea of innate strengths and weaknesses and targeted attacks never factored in. Even the original Megami Tensei, whose sequels largely revolve around hitting enemy weaknesses, offered a barebones, Dragon Quest-like assortment of magic for its spellcaster to use. In the wake of Final Fantasy, however, the rock-paper-scissors of elemental affinities and spell groupings became standard issue for RPGs.

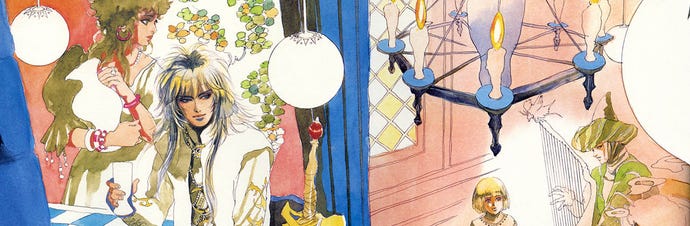

Despite his influential design decisions and prolific creative streak, most American gamers didn't get a proper taste of Kawazu's quirky design sensibilities for another decade. His projects — namely the Romancing SaGa trilogy for Super NES — never made their way West. Neither did the Final Fantasy sequel he directed, Final Fantasy II; it was passed over for localization, along with Final Fantasy III, in favor of jumping ahead to a renamed Final Fantasy IV. And while his two projects that did see English versions (the first two Final Fantasy Legend games) were decidedly unconventional RPGs, it was easy to write off that strangeness as an attribute of their portable nature. Of course Game Boy RPGs would be weird, we assumed, because the system itself was so underpowered and limited!

Early in 1998, however, Square and Sony published SaGa Frontier for PlayStation in America. Having recently been turned on to the concept of RPGs by the wildly successful Final Fantasy VII, a remarkable number of role-playing neophytes flocked to what was sure to be the next amazing work from the creators of FFVII. They were promptly bewildered. SaGa Frontier lacked the stunning visuals of FFVII, along with its cinematic presentation, larger-than-life characters, and bold in medias res introduction.

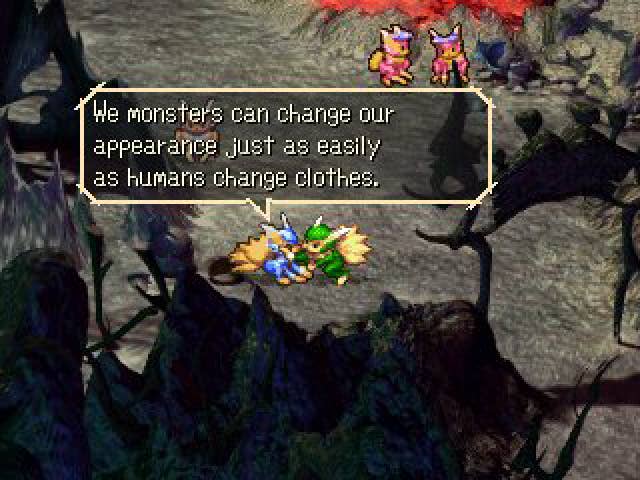

In fact, it lacked something as simple as a basic sense of direction or purpose. SaGa Frontier told seven different stories with seven different protagonists, playable in any different order. Some were lengthy adventures, while others could theoretically be completed in a matter of hours. Most quests overlapped with one another, covering much of the same ground, even allowing you to recruit main characters from other storylines as party members. The world consisted of a hodgepodge of influences ranging from surreal fantasy to pan-Asian cyberpunk cities ripped straight from the pages of a William Gibson novel.

And then there was the battle system. The characters had such weird traits! Monsters would mutate seemingly at random. Party members would fall in battle but immediately stand up again, despite having zero HP, only to suffer some weird new form of damage that eventually led to their permanent death. Occasionally characters would learn new skills denoted by a little light bulb above their heads, sometimes performing combo maneuvers with the rest of their team. But always — universally — without warning.

While FFVII built to a certain degree on Kawazu's love for core tabletop mechanics to create something accessible and fun, SaGa Frontier embodied a different passion: Discovery and evolution. Kawazu's games, above all, find unity in their emphasis on character growth through player action. In offering the player extensive choices and opportunities. And most of all, in never once explaining how on earth all these things work together.

A quick survey of Kawazu's body of work reveals the truth of this. Final Fantasy II, for which Kawazu took the reins as lead designer, abandoned character levels and traditional level-ups in favor of incremental improvements based on individual party members' performance and actions in combat. The Final Fantasy Legend games — actually the earliest entries in the same series as SaGa Frontier — mixed things up by making some characters solidly predictable and others subject to what appeared to be random transformations. The Legend of Mana introduced a huge array of seemingly superfluous systems (such as building golems and farming pets) that did little to affect the core game but offered potentially vast rewards to those who took the time to master their intricacies. The Last Remnant applied the principles of SaGa to large-scale warfare. And Unlimited Saga was weird even for a SaGa title, a virtual board game with wildly unpredictable outcomes for each turn.

And yet, for those who take the time to properly sort out how everything in these games fit together, Kawazu's games offer addicting depth and substance. The biggest crime his games commit is ultimately not to offer much guidance to the player (or, in some cases, any guidance at all), leaving those who happen upon these creations to struggle through the fundamentals themselves.

Perhaps that's why Kawazu's best-received works to date have been the ones that make their expectations self-evident; the PlayStation 2 remake of Romancing SaGa, for example, featured all the idiomatic excess of Kawazu's standard fare but did a great job of explicating it to players. Likewise, the (sadly Japan-only) remakes of the Final Fantasy Legend trilogy took pains to lend some transparency to previously baffling features — something as simple as giving a preview of the results of monster mutation went a long way toward reducing the frustration of those games.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the most successful of Kawazu's creations in the West have been the Final Fantasy: Crystal Chronicles games. In many ways, they're the opposite of SaGa; there, abilities like magic derive self-evidently from equipment, and character levels have a diminished but predictable role. Even so, the original Chronicles had his fingerprints all over it in the form of the strange "bucket" mechanic that required player parties to drag an artifact with them at all times to provide their heroes with a zone of safety in which they could act without penalties. This ultimately proved for many to be a frustrating and limiting design choice... but it sure didn't resemble any kind of mechanic seen in any other RPG.

What makes Akitoshi Kawazu's work so interesting is its deliberate refusal to fall into step with trends and traditions. His design choices often come across as counter-intuitive, even destructive, seemingly crafted to annoy and frustrate the player. He's clearly a man working to his own distinctive vision, designing games that suit his own tastes and whims. At times, this can result in something approaching genius; at others, it merely confuses. He's the Ed Wood of game design, crafting bizarre and sometimes even unplayable works that nevertheless display a spark of genuine, if slightly mad, creative passion. His works are as punishing and bizarre as the man himself is quiet and good-natured.

There is no other game designer who shares Kawazu's unique design obsessions. And while that can make his creations frustrating, it also makes them wonderfully fascinating as well. Though his role at Square Enix is more that of executive than designer these days, we can always hold out hope that he hasn't produced the last of his inexplicable, unintuitive RPG concoctions. Game auteurs are too precious to squander on the boardroom.