Ghost Recon Wildlands - Layer by Layer

A look into Ubisoft's work in crafting the South American landscape of the newest Ghost Recon.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Building Bolivia, Layer by Layer

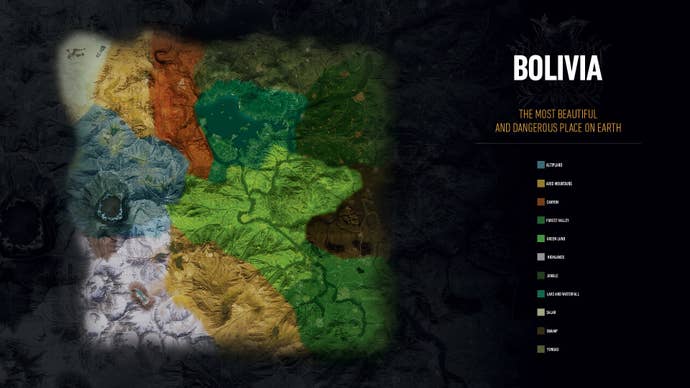

Once the in-person research was done and the style guides for the artists were completed, Ubisoft Paris set to work building the region in-game. The final product is a sprawling digital representation of Bolivia, stretching across 11 ecosystems: Altiplano (high plains), Arid Mountains, Canyon, Forest Valley, Green Land, Highlands, Jungle, Lake and Waterfall, Salar (salt flats), Swamp, and Yungas (mountain jungles). Digital Bolivia is home to 7 million different trees, bushes, and rocks, 800 kilometers of road, 150 kilometers of railways, and 120 unique settlements.

The numbers don't capture the scope of the technology needed to build Ghost Recon's Bolivia though.

"It's not just a game about trees and rocks. A lot of ecosystems, a lot of diversity, a lot of detail, and a lot of tools to be able to create all that content," says Martinez. "When you start from all this material, you have to ask from a technical point of view, 'Where do I start?' First, we will decide what is our Bolivia, how do we recreate that to have all the possibilities and diversity we see there? How do you make that all exist, be consistent, and blend nicely? That's why we need so much space on the map, because we want so many environments. If we put everything too close together it's like mini-golf."

A Natural Ecosystem

So Ubisoft Paris began by molding the landscape from real reference maps of Bolivia, to maintain specific iconic features of the terrain. Once the general terrain was laid out, they began to paint the major biomes: jungle here, altiplano there. Where does snow appear and where will the rivers flow? Each biome had an inspiration from a place that stood out during the research trip.

The next step was breaking out the world logic, looking at the specifics of animals, wildlife, trees, and more. How do people or animals live in a specific region? What plants occured naturally? Where are the borders for each province? What about the landmarks or the daily activities for the local populaces, because those who live in the jungle have a different lifestyle from those who live in the dense cities? Martinez tells me that Ghost Recon has "a full agenda for the NPCs." They sleep, go to work, and generally go about their days.

Ubisoft Paris had to break the logic the world down into component parts and then rebuild from the ground up. When they did so, they built everything in layers.

"First of all, you start from the ground," he says. "Define the terrain and on top of the terrain you sculpt it with mountains and fields. You add vegetation on top of that and you have a full natural landscape before any humans arrive. Then you start to add railways and connect roads. Then the villages come and flatten the terrain a bit. Then you add details."

As Martinez explains it, Ghost Recon Wildlands' map is build from a total of six major layers separated into two distinct groups. Within the first group, Nature, there are the layers for terrain, rivers, and vegetation. Then there's the Construction group covering man-made items, including railways, roads, and villages.

"We worked with a lot of specialists in the beginning. We worked with people coming from universities that told us everything about the plants," explains Martinez about the early process of understanding the world logic. "Then we went there to study the real location. After that, you have to make some choices. Decide what's the most iconic, what kind of trees you want to recreate. We try to match the photography, so sometimes it's not totally accurate to reality. Do we need to change the reality a bit to reach our goals?"

"For both categories, you can define rules," he continues. "Why are there mountains there? Why is there river, how does it work? How does the river sculpt the terrain? What's the logic of the village and what's the logic of the road? If you start with the rules, you can have a huge piece of landscape and you can see that it really flows. It's not fully-simulated, because you have total control with what you are doing, while still being as realistic as you can."

Ubisoft looked at everything. When it comes to rivers and lakes, the system takes into account erosion and the water line, which then affects the rocks and foliage that's placed in a region. For vegetation, placement is defined by soil, altitude, steepness, proximity of water, sunshine, and overall biome. An algorithm is in place for each object, so Ubisoft's tools can automatically place items in the world. All of this world logic is necessary for building at such a large scale.

"If you can define all those rules, you can start to fill all your layers. I don't mean automatically, but with specific tools," Martinez says. "At least, you can share the same methodology with your team and everyone can speak the same language. You can unsculpt it, because you know what you're doing, or you can start to define an algorithm to help the artists to take care of this huge landscape. To be consistent across the world, because if you have enough artists sculpting the terrain, each in their own way, you won't have a consistent result."

"For each tree, we decide we're going to use this tree in this biome, between these altitudes," he adds. "How does the sunshine effect the trees? We can compute that. We can decide when we create the tree: if those trees are mostly in the shadows, they're probably going to be weaker."

The same tools are applied to placing rocks on the landscape, with certain rocks appearing on cliffs or steep slopes. Ubisoft's designers and artists can add all these objects by hand as well. Martinez frequently mentions "sculpting", noting how the artists can make large changes and let the logic take over, or get into the details and move things around. This is necessary, because Ghost Recon Wildlands' world is built in the service of gameplay.

"On play stuff, we need to be really precise in the case of a mission or if you're really close to a camp," says Martinez. "We have tools that help us to define these kinds of rules to place larger-scale content. Always, we have a lot of control. We redefine: I want this distance between each tree, so we're sure that it's going to make good cover for the player. The key was for artists to have maximum control, but to create in large scale. Control from the grass blade to the mountain."

Gameplay first is the primary motto of the Ubisoft Paris team. Looking good is one thing, but it needs to play well too.

"At some point, the artist in charge of placing the rocks went a bit crazy," Martinez tells me. "It was looking really good, but when you were going off-road with your vehicle it wasn't great, so we had to refine our strategy for placing rocks. Gameplay first."

Artist control is important for processes like blending each region. Ghost Recon Wildlands needs to feel natural when you move from jungle to desert. Ubisoft Paris may have started with terrain from the real Bolivia, but the game world had to shift to accommodate gameplay elements. This sometimes means increasing or decreasing the size of regions.

"How big is the range we're going to use to blend from this area to this area?" asks Martinez. "Blending from the Yungas, the jungle in the mountains, to the jungle in the valley, you don't need too much space because it's quite similar. The transition can be quite fast over a few kilometers."

"If you transition between two areas that are quite different, you need more space to just blend and stretch, so you're not driving or walking and suddenly everything changes. When you're going through the game, you shouldn't realize that you went from one setting to another. It has to be real smooth," he says. "We have two kinds of places in the game. We have the wild and we have the places that have been more designed for specific missions. Most of the time, you're in-between."

Everything is reviewed and iterated on internally and Ubisoft's tools allows for vast changes or small shifts in the game's world.

"We work with very good artists, they're very experienced. We can trust them to make the right choices, but we have a lot of reviews internally. We will study the location together, carefully chose the references, then the artist will start work, and then we'll have review. It's a very iterative process," says Martinez.

Given the desire to make Ghost Recon's Bolivia feel real, I wonder about the edges of the map. While the real-world equivalent goes on forever, the game's map has to end at some point. Martinez says that they do their best to illustrate the end of the play space, using natural landmarks and regions.

"That's something that we had to take care of from the very beginning," he tells me. "There's no one solution. It depends on the location. One side of the map, we end in the desert. On the other edge, we end with some water or cliffs. But at some point we have to tell the player 'You're going a bit too far.'