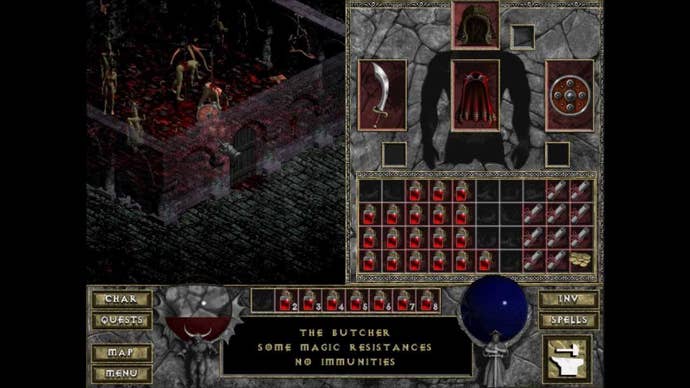

An Oral History of Diablo II With David Brevik, Max Schaefer, and Erich Schaefer

The battles with Blizzard, the year of crunch, and the shower ideas behind one of gaming's most enduring pillars.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

A little more than fifteen years ago, Blizzard North set to work on what would become one of the most popular and enduring action RPGs ever - Diablo II. Finally stable after the success of Diablo, Blizzard North looked to create an even bigger sequel. The project's principals included David Brevik, Max Schaefer, and Erich Schaefer - Blizzard North's co-founders and the designers of the original game. They eventually found themselves mired in an overwhelming project, one in which they found themselves working 18 hour days to complete.

Here, in their own words, is the story of the development of Diablo II, and what it was like to be at Blizzard North in those days lasting from early 1997 to mid-2000.

January 1997: The Aftermath of Diablo

Diablo was released on December 31, 1996. It was met with critical acclaim, validating a difficult development process that had put Condor on the brink of insolvency several times. Following their acquisition by Blizzard and the subsequent success of Diablo, the newly-renamed Blizzard North began looking ahead to the future.

Max Schaefer

It was a very weird time for us, because we signed to make Diablo first as an independent contractor. We were not part of Blizzard when we set out to make Diablo, and about halfway through they decided to buy us out. But that really changed the project entirely, so we almost started over halfway through, because now we were part of Blizzard, we didn't have any budgetary constraints like we did before.

And then they added on the whole concept of doing Battle.net to it, so it was a time of intense change and action. All I remember in the aftermath was that it was so foreign to us the way that it kind of blew up before we put it out, that we were all kind of waiting to see what happens now. I remember that sense of, "Well, what happens now?" That's the thing I remember most about it, is the anticipation of this great unknown sequence of events that was now going to take place.

Erich Schaefer

Yeah, I remember the immediate aftermath. We were crunching trying to get it done leading right up to Christmas Eve. We took Christmas Day off, and then came back in on the 26th thinking, "OK, here we go, let's tackle the rest of the bugs, let's try to finish this thing up." And I remember that that morning it turned out we were pretty much done. There were no more deadly bugs. So, we were like, "OK. We were sitting there on the 26th, kinda, we're done, what do we do now?" And that just felt weird, because we were in such a daze from such a long crunch to get the thing done. Should we just send people home? Should we take the week off? It was kind of a weird haze going on and nobody knew what to do.

So, we did end up pretty much taking the rest of the week through New Year's, then came back and said, "Well, I wonder what's going to happen."

Max Schaefer

It was no foregone conclusion that we would do a Diablo II. In fact, I think that we had decided that it would probably be fun to try something else. But, with the obvious popularity of Diablo 1 and lack of a clear idea of what else to do, I remember we did make a pretty quick decision that we were going to launch into Diablo II, and do it in a way that addressed some of the issues that were coming up in Diablo 1. We had no idea that people were actually going to play this game, much less try to cheat it. I think we kind of launched the advent of cheating in internet games.

Erich Schaefer

It didn't take us too long to get to [the point of wanting to make Diablo II]. I think, as I recall, and this is a long time ago now, I was sort of always pro-Diablo 2. Even at the end of Diablo 1, I had a big wish list that sort of turned into the Diablo II design document of what we would do from there. So, I figure it was more relief that everyone else got on board from my point of view.

David Brevik

We were all really happy with the success of Diablo. It was much more successful than we imagined it would be. But, we were kind of ready to move on to Diablo II because of some of the problems with Diablo 1. When we made Diablo 1, we just put in Battle.net, and we made it multiplayer about six months before we released the game, and it was peer-to-peer, not client-server, which means that every computer is in charge of all of its own information, including your character, so, it could easily be hacked.

And when we made Battle.net, we knew the Internet existed and all this kind of thing, but it was like, if someone wants to hack their game, it's fine. They can ruin their own experience. But, then we realized, oh, crap, they can take that hack and they can put in on the internet, and now everybody has it. It wasn't just one person who was going to ruin their experience. So there was a real desire after seeing some of the feedback and seeing what was going on with the hacking to fix this in a real way. Given that, the team was pretty excited about moving on and working on a second version that we had the time to do a better job. We could do more as far as streaming levels, we could do more as far as keeping it in the world in a more cohesive faction, as well as put in running and some of these things that we really wanted that didn't make Diablo 1, but were things that we wanted all along. And, so, I think the team was really eager to do that.

So it was an exciting time. People were really happy with the success. Things were really good for Blizzard in general. StarCraft was on the horizon, so it was a really fun time.

Erich Schaefer

We moved offices a couple of times in that period. I'm not sure exactly when the happened, but I think we finished Diablo 1 with about 14 or 15 people on the staff, and then finished Diablo II with about, I'm going to say about 45. And I think there was a pretty steady ramp. We didn't immediately hire up a ton of people to get going. I think it was sort of a steady ramp up during the Diablo II development.

The number one personality was definitely David. Without him, there's no way this could have ever happened. He was the fearless leader of us all, and drove the development day to day, especially when things were going weird or we had to get back on track. So, I think, to me, he was the shining leader that made this thing work out. He had the technical skills to get anything done when we did have a hump, when it, oh, it turns out we were going to make this game a multiplayer game, or we were going to turn this thing that started out, famously, people talk about as a turn based game, it became real time halfway through, and it only took Dave about a day to do that.

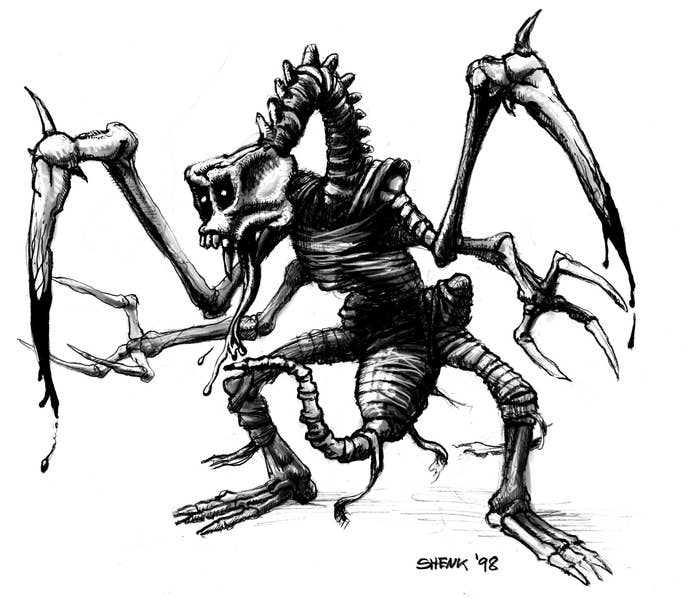

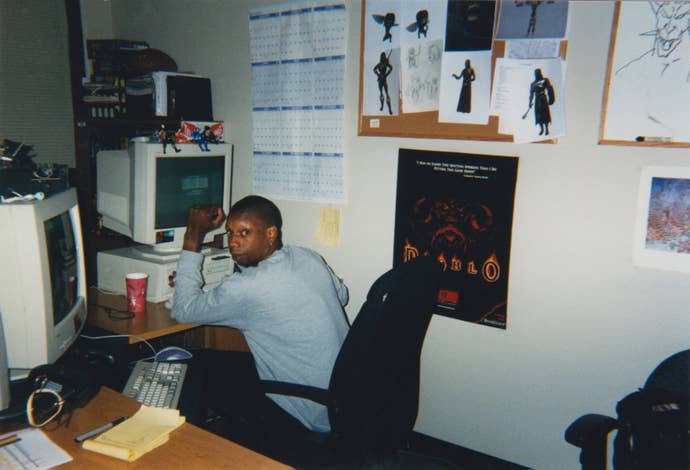

We had a great crew of artists that I loved working with. Michio Okamura was our character artist, and just loved working with him. We went back and forth with character designs all the time. He designed the original Diablo himself, and most of the monsters. We actually hired him when we were doing superhero games, and I don't think he had any job experience before that. We were doing the Justice League Task Force game, and he could kind of draw superheroes. So we kind of based that art on his drawings, and then he transitioned right into the Diablo stuff really well.

Rick Seis was sort of Dave's right hand man, programmer, great guy to work with.

Max Schaefer

It was a different time then. We hired a weird mix of friends of ours from the past and guys we had just met. [Erich] mentioned Michio... Michio didn't work a computer. He did line drawings that we would turn into things, and he did character designs, all just by hand. He was a tremendous artist. We hired other people that had rudimentary computer skills, but it's not like today, where you come out with a Master's degree from some university in some of these topics. Everyone was sort of self-taught and just winging it. It was a very colorful group of guys, and we were all doing this for this first time, and we were all just seeing where it went. So it wasn't like, again, today, where half the staff has worked on other major titles, everyone is super well-trained and specialized. It was definitely more free-wheeling back then.

But, it was really tight at that time. I think as we grew into Diablo II, we got a little bit more into factions and issues and troubles, but back in the early times when there was just the 14 of us, or whatever it was, we would hang out together after work, and we would play NHL Hockey tournaments on the Sega Genesis in the office.

When there's only that many people, you know everybody, you talk to everybody every day, you hang out after work, and that was... I remember that being very good times. A lot of those people, it's funny, are still in the business today. I think that we kind of represent an old guard, but there's a lot of those guys are still making games and still doing this as a career, even though, when we started that, nobody had thought of this really as a long term career.

Erich Schaefer

One guy we should definitely mention too, that Max still works with to this day, is Matt Uelmen. He did all our sound effects and stuff back in the day, too. He came on early, maybe our fifth or sixth hire, even though we weren't sure we even needed a sound or music guy. But he kind of hassled us so much that we finally hired him, and he's just a great guy to work with, and we still work with him to this day, at least at Runic. Just a brilliant musician. Usually the smartest guy in the office on a lot of topics. But just also the classic music guy. He has a lot of eccentricities and personality quirks. He was also an incredibly good tester. He could figure out how to exploit or break your game better than anybody.

Max Schaefer

We hired a lot, we had to fill out a staff quite a bit at this point, so there was Stieg Hedlund as a designer, the Scandizzo brothers, lot of guys. Yeah, I'm just thinking back. It got a lot bigger for Diablo II. It was a lot bigger task, and we were trying to do a lot more. We had to get a bigger office, and then we got a bigger office than that, after that. So, yeah, it was a time of growth. Probably a little bit more management than we were used to.

Erich Schaefer

None of us had any management experience, and kind of still don't. We did a lot of things wrong. I think the classic thing we did wrong was just mis-managing the time and the scheduling, and we started to crunch to finish the game, what, a year or two, a year and a half before it came out, thinking that, hey, we're pretty close, we're four months away if we can really push and get this thing done. And then after about four months of crunching we were nowhere near, and we had to call an end to the crunch for a while. So, that was just classic time mismanagement and just a bad prediction on our part. Happens all the time, but I think that was one of the worst examples of all time that I'm familiar with.

Max Schaefer

It all kind of stems from, you start into a project like this, and you realize all the cool things that you can do. And we're like, well, we have the money and the time now, so why not add this feature or that feature? And it just adds up quickly, and all of a sudden, a two year project becomes a three year project, and like Erich says, we spent way too much time crunching at the end. Actually, some of the darker times was the end of Diablo II, just because of the growth of the company and the growth of the project to the point where everyone was having to work seven days a week, all waking hours, for almost a year.

Planning and Production: New Worlds

Blizzard North had big dreams for Diablo II. After taking a few months to recover from the grind of Diablo, they returned to begin work on the sequel.

Erich Schaefer

The first six months were very slow. Through the middle of Diablo 1, the company had a very relaxed atmosphere. We would spend the whole day playing other games. We would all take trips to go watch movies, and go to Fry's and pick up the latest games. In a way, we wasted a ton of time. I think it was a good waste of time, and fun, but finishing Diablo 1 was such a grueling experience for us, especially, having not really done something that big before that, we took it real easy the first six months of '97. We got back and just goofed around a lot. So, imagine, once you get into that mode, it takes a while to ramp back up. So I think it was a bit of a slow sluggish start. I wouldn't say it was bad, though. I think we needed it.

Max Schaefer

Yeah, we needed it. And there's always this time when you're working with new tech and new systems, that it takes a while for the programming staff and the engineering staff to have things in place for the designers and artists to actually work on stuff. So it's kind of natural between projects that there's a little bit of downtime. But it's always a bit of a challenge to get it ramped back up.

Erich Schaefer

I think by the second half, and again, this is a long time ago, but I think by the second half, we had a solid Act 1, we had the town, the surrounding landscapes, and I think the initial dungeons. And I think we had all that stuff by the end of '97, so we really had our feel and our look and knew what we were doing by then.

We went back and forth a lot on whether we should wait to announce until we were almost done, or whether we should try to build hype early on. I do remember, there was concern that we were announcing it too early, but at the same time, I remember we announced StarCraft so early they didn't even have a game. They literally had some placeholder art on top of the Warcraft engine. And it looked completely different.

And so, at the time, we were like, "Hey, let's just announce these things, and build hype from the very beginning. Maybe it even gives us a little push to get the game done ourselves."' And then, after those two examples, Diablo 2, which was announced way too early, and StarCraft, which was announced before they even started, I think we then changed tactics and kind of said, "Hey, let's just wait four months before we know the game's done." But I know they've gone back and forth since. Most of those we do consider were announced too early, though.

Max Schaefer

Yeah, although, we did have some extra considerations with the Diablo 1, because it wasn't too long after it was released. It was gaining popularity, and we realized that we were dealing with a pretty significant cheating problem that was impacting people's online experience, and we wanted to have an answer for that. We wanted to say, "Hey, yeah, for Diablo 2, we're going to a client-server system instead of a peer-to-peer system, that should take care of it." We thought it would be easy to take care of the cheats then. Not so much. But, we did want to have a public message to address it, and part of that was, "Hey, we're making Diablo 2 now, and it's not going to have this problem."

Erich Schaefer

We had this wish list where we wanted to go [with Diablo II], and one of the obvious things was that we wanted it to not just be one town with one dungeon. We were going to make it throughout a series of lands. We ended up with three, plus the finale in Hell, but, we didn't really know. So, at first we were sort of just compiling a lot of visual ideas and where we wanted to go.

David Brevik

One of the things that we wanted to do that never got done in Diablo II was that we were trying to design this thing called Battle.net Town. You know, my idea was to get into a world, and you don't leave the world. I wanted to try to break that reality, break that illusion that we're not in a contiguous world. I wanted you to start in that world, not start in the Battle.net chat lobby, but start in that world. And Battle.net Town was going to be a glorified chat room where you could move around, but you could still go to the pub and chat with people, or go to a vendor, and then you would go to a specific person and you would travel to Act 1.

So, you never left the world, and that was kind of one of the things that didn't make it, but that was one of the things that we wanted the most, that I personally wanted the most, which was, I really wanted this kind of, more of an immersive world feeling to the game than we had, and make it more expansive. We're not just in the dungeon beneath this town, that there's a big world out there.

"There was no definitive design document [for Diablo II]. There was a loose structure. "Hey, I know we wanted to go here for Diablo 1, this is kind of the first act. This is kind of the story we're telling there." And then we get to the second act, and "Hey, where do we want to go," and then, "Oh, I got this idea for this level, it's going to be in space, it's going to be awesome." And we'd mock it up. "Yeah, that's great. Doesn't make any sense in the story, but what the hell, it's kind of cool." - David Brevik

We had been playing Ultima Online, and that had definitely some influence on this design, where you could walk from one part of the continent to the other. I was thinking, "Wow could we do this and mix it with Diablo?" And that was the way that we wanted to go, but we never really fully realized that dream. We got pretty close, in that we were able to stream a lot of the levels and things like that, but we never got to the point where you could go walk from the Sisters of the Sightless Eye Cathedral to the desert or whatever. That wasn't really fully realized for Blizzard until World of Warcraft.

Max Schaefer

The biggest thing was that we had the outdoors. We were going to expand from just levels of dungeon underneath a church and do real landscapes, real outdoor landscapes. So I was tasked with organizing the background team, and that was by far the biggest topic for us: "Now that we're going to be outdoors, what does that mean? Where should we go, where should we take this?" It really came down to, where would it be cool to be? It would be cool to start out in the Irish countryside, just like Diablo 1's town was in. But then, it's wide open, we should do desert levels, we could do rainforests or whatever. I think, again, we might have been one of the first, setting a long, now, long tradition, of having your second area in an RPG be the desert. You see that all over the place now. People start out in sort of an Irish countryside, then they go to a desert, then they go to something else. I remember, it was a whole lot of fun just pouring through books and looking at landscapes and looking at architecture and deciding where we wanted it to play. Where did we want to kill monsters?

I think doing a desert is always challenging, because it's mostly sand, and so you have to break it up with enough features that it's interesting. Sort of the same with a rainforest, in that it's so densely packed with foliage that you kind of have to find clear areas that you play in. It's sort of the opposite of the desert. Instead of trying to invent stuff to constrain you and keep you along the path, you have to clear out areas and make it plausible that you're in a rainforest, and yet you can see your character and there's room to fight monsters. To that end, we had the rainforest mostly take place along a riverbed.

Erich Schaefer

That sort of reminds me of another challenge we had. The gameplay was fine in the dungeon in Diablo 1, but we were bringing it to the outdoors with just wide open fields. We asked ourselves, "What are the boundaries? What are the obstacles?" If it's just a field, there's no real tactics where you move around. So we put a lot of work into what should the sizes of these outdoors be and giving them boundaries and borders that made sense so you didn't want to wander forever. So we came up with all kinds of weird low walls that surrounded a lot of our outdoors that don't really make any sense. I remember at the time a lot of people were very negative on it. It was like, why couldn't we just hop over the walls? Itt's going to drive people crazy that we're limiting their area. I thought it was a big concern. Turns out, it felt really natural, and I don't think it ever got brought up again. The idea of taking it to the outdoors was one of the big early challenges.

Max Schaefer

And it took a lot of iteration, too. I remember we had way too big an area for a while, and claustrophobic areas. It took a lot of testing and play to figure out, when do you need a choke point just to reorient everyone along the path, and how big an area was it before you miss things or you're lost or you don't know where you've been? It was just a lot of play back and forth and tweaking of the size of things to get it right, because it is really different being outdoors than being down in a dungeon.

Erich Schaefer

Also, we had to invent, as far as I know, we probably invented the idea of a quest log to keep track of what quests you were on, which ones you had finished. For ourselves, at least, we had to invent that. There was no such thing in Diablo 1. It was just, you could do whatever was there, basically. There were some quests, but they didn't really operate in parallel, and you couldn't track them and do them or not to them. So, that was all new territory: how people know what to do, where to go. The waypoint system for getting around, we had to invent all that stuff. So, none of those were in the design document. They just kind of... they were problems that came up as we started to play, started to make the big area, and we were walking out there in the field. Hey, how are we ever going to get back to town? How are we going to get back to here? Those sort of things came up as we developed, we didn't plan them out beforehand.

David Brevik

There was no definitive design document [for Diablo II]. There was a loose structure. "Hey, I know we wanted to go here for Diablo 1, this is kind of the first act. This is kind of the story we're telling there." And then we get to the second act, and "Hey, where do we want to go," and then, "Oh, I got this idea for this level, it's going to be in space, it's going to be awesome." And we'd mock it up. "Yeah, that's great. Doesn't make any sense in the story, but what the hell, it's kind of cool."

So, we'd put that in, and then, "Oh, let's go to the jungle. And we'll have little tiki men," or whatever the hell you want to call them there. Little goblins. And we'll have frogs and stuff. And then eventually, we knew we wanted to get to Hell, and what that would be like. We had sort of a loose structure to it, but there was no definitive design document, no specific things. Every day we would just iterate on it and change it how we please. And it's like, "Oh, I got this great idea, we're going to change it to be this way." And that was really more the way that we operated. It was like, as we played the game, we designed the game for features that we felt would be interesting additions to what we're doing, or make whatever it is that's broken better.

Erich Schaefer

Yeah, I think, actually, that's not that strange. We've never had, in any of the games since, the Torchlight or Hellgate or Rebel Galaxy here, I've never done a design document. Maybe that's my failure as a designer, in a way. At times we sort of fake one almost. We kind of said, "Let's just make sure that new hires have some idea of what's going on, or whoever our partners are have some confidence that we have anything." But, all our games, we've just sort of made as we go along.

Max Schaefer

It's part of our style that we try to have a running build going all the time, so that we can proof our concepts just basically by playing what we have, and it becomes readily apparent when everyone's playing the build what it needs. Do we need more variety in backgrounds, do we need certain kinds of monsters for this area? Once you have the framework in there, the details kind of fill themselves in.

Erich Schaefer

We sort of just plan for the month ahead, or the week ahead, even, at all times. "Hey, we need more monsters in this area, let's get a batch of monsters going." And again, I've said it a bunch of times, the iterative style where you, we constantly just evaluate the game. What's fun about the game, what's not? If this isn't fun, let's get rid of it, let's replace it with a different thing. And if we had a design document, we might be working on that thing that wasn't fun forever. Without the design document, we don't have to worry about that. At the same time, it makes bigger teams much harder, of course. It's hard to manage leads that then have to talk to their group and schedule out months ahead. That's pretty hard to do in our style. That's why, I think, that's why right now I'm working with two guys. It's just me and [Double Damage Games co-founder Travis Baldree], and it works fabulously with this iterative kind of style.

But it really takes some key people on the team, again, Dave Brevik is the great example with Diablo, to be able to just adapt on the fly. He will fix things that morning and get us going for the rest of the week on this task. So, it's very designer developer heavy, and not producer heavy, style. We did run into trouble and got too big, and Blizzard North, even after Diablo 2, got even bigger and ran into some real troubles with this style, but I think the style is key for my enjoyment and it worked out for our best game, so I think it's good, even though I wouldn't exactly advise it.

The Birth of the Skill Tree and the Development of Diablo II's Classes

The skill tree is now commonly known as an "RPG element," but it didn't become a genre fixture until Diablo II. As with many of Diablo's best ideas, it came to David Brevik in the shower.

David Brevik

One of the things I became infamous for is that I would often come in, and, I don't know about often, but every now and then I would come in and say, "So, I had this idea in the shower this morning." It was like, "Oh, Dave's shower idea has hit the game hard, because it's some major change to the game."

Erich Schaefer

At some point early on we went with the skill tree idea. We didn't start with that. That was a brainstorm by Brevik again. He was like, "Hey, let's make skill trees that are similar to tech trees in [Civilization II]," which I believe we were playing at the time. So that sort of set the pace. Then we started to think, "OK, what would be on the trees for these various characters? Should they have shared abilities like they did in Diablo 1, or should they have their own skills entirely?" I think one of the cool things, before I get to the specific classes, again, I think we kind of came up with this. I'm sure there's examples, but at least for ourselves, of, the warrior classes use spells just like the mages. So, before that, warrior classes in RPGs would just come in and hack on guys. Maybe they had some ability or something, but they didn't have a raft of skills they would commonly use like we ended up doing in Diablo 2.

David Brevik

I have no idea where I thought of that idea. I mean, again, I thought of it in the shower. But I don't know where it came from. It came from, I didn't like the way that we were, how we were going up levels and getting these skills, and it didn't feel like there was enough creativity or choice or things like that. We wanted to give people this sense of, "How do I choose how to play my character?" We had all of these skills, and it was kind of a mess, and there was all of these potential builds, how do we organize it in such a way that allows the people to easily identify?

One of the great things about Diablo 1, but one of the problems with Diablo 1, is that, from my hardcore nerdy perspective, you could make so many different builds, because everybody could do everything. But from kind of a general audience view, they were overwhelmed with all the possibilities. So we wanted to narrow that down into classes, yet still give a lot of flexibility within that class to kind of customize yourself and make you different from everybody else. And that's really the concept behind it. It was, "I'm going to make my character very different, even though I'm a Paladin and you're a Paladin, my Paladin plays very different from your Paladin, because of the choices I've made." That was really where the idea came from, and this was just a way to organize that idea.

Max Schaefer

I remember even on a fundamental level, kind of one of our goals with the character classes is that they would be slightly different than the stereotypical RPG character classes, but recognizable enough that you would know what they do. You should be able to look at the character and kind of get a sense of the way they play and what they do. That was a principle that another one of our key guys, Matt Householder, termed "familiar novelty," where you're seeing something new that you haven't seen in a game, but you understand what it is right away.

David Brevik

One of the things that he did that was really good for design for us was the way that he sort of set up the spreadsheets, because we used Excel to do all the data. And the way that we set up the balance, and the way that we did skills, I think [Stieg Hedlund] really brought that with us. So, we were able to put in more content with the way that he designed the way that we were going to do the data stuff for the levels and the difficulty, and things like that. That was definitely a big factor as well, because he helped to contribute in many other ways with design on all sorts of stuff, from monsters to whatever, all sorts of things. A lot of the radical ideas, more radical design ideas came from either myself or Erich Schaefer, I would say, the most.

Erich Schaefer

The classes themselves developed during play. I think it was largely Dave and I saying, "Hey, what would be fun to do with this guy?" and just cooking up skills on the fly; but a lot of times, most classes had advocates in the office, and people were big Paladin fans, or big Necromancer fans. They would just throw out ideas to do. The classes developed as we went based on the artists, Kelly Johnson making some of these characters. Just the way he moved, and the way that they sort of looked, kind of developed, "Hey, this is what this guy would do. Obviously he would have a shield slam." So, I think, again, a cool part of our iterative process is just like, "What would be fun to do with this character now? How can we go even more gonzo when he levels up, and gets even cooler things to do?"

I can't remember any sharp disagreements [over classes]. I remember at the end, when there was a lot of concern over balance, and I remember, I'm not going to name names, but, people would say, "This skill is way too good." And we would argue about the balance of skills. And I think we ended up patching the game many times, but there were some really bad balance problems, due to just kind of weird arguments at the end, and since there were only two or three or four of us who really had in depth knowledge of how to play these characters towards the end game, we made some weird decisions just based on personalities. I don't remember, I think everybody was pretty much on board with the looks and the feels of the characters as we went along, though.

Max Schaefer

I remember, I think we did spend more time going back and forth, I think, on the look of the Sorceress. That was championed mostly by Mike Dashow. It ended up wonderful, but I do remember going back and forth on that. Paladin looked great from the get-go. The Barbarian too. Necromancer was such a weird class, nobody had any expectations or really strong feelings on what he should look like. And, what was the other one, the Amazon kind of did herself as well.

You start with concept sketches, and then first in-game models, and, there's always a little bit of, "Hey, that didn't look like it did in the sketch. Why is that?" "Well, our camera angle and the scale makes it such that… That type of clothing doesn't look right anymore… Or, the way they move or walk looks a little bit weird." And normally, you put it up on screen, and everyone agrees, "Hey, that doesn't look right." "OK, we'll go back and fix it." And that's just the standard way that things work. I know we worked on the Paladin's animations for a while, because his look didn't look quite right, but his walk was always spot on. I maybe even have an incorrect memory about this, but I remember we went back and forth about the Sorceress quite a bit before it was nailed down.

Erich Schaefer

Yeah, and I kind of remember a lot of joking that it looked like the Necromancer was wearing a skirt. We ended up leaving it, because enough of us liked it, but that was, not necessarily a contentious point. But it was pretty funny.

David Brevik

It's amazing how many new standard things came out of Diablo and Diablo II. It surprises me all the time. The rarity thing [for loot], for example, just kind of made sense. In some roguelikes, they would have your common item and your magic item, so they were different colors of text or whatever. If it was a magic item it was blue, if it was a normal item it was white, that kind of thing. And, so, we took a step further and went with the rarity levels. The rarer something is then it has a different color. That really has stuck with games, and then they took it to a whole new level with World of Warcraft, and it really became standardized roleplaying stuff ever since then.

The Big Crunch

As Diablo II's development rolled into 1999, Blizzard North pushed hard to have the game out by the end of the year. But no matter how close the end seemed, it always remained just out of reach. As the months passed, they found themselves mired in what seemed like a neverending crunch.

Max Schaefer

It was probably June of '99 that we started the crunch in earnest, the real, seven days a week, all waking hours, driving home at midnight and coming back at eight.

David Brevik

With no real deadline, and no real way that we were managing our time, because we didn't estimate any tasks or anything like that, we just didn't estimate our time correctly. And the thing that sucked about that, though, was that we knew we weren't going to make it at our current rate, but we believed that we could do it if we just started crunching, we believed that we could make the end of 1999. And so, we started working really hard on meeting that deadline, and we started working, I was working every day. I took off, the last year of Diablo 2, I took off four days the whole year. I worked every other day, and most days I averaged about 14 hours a day.

So, we worked incredibly hard to try to get this thing out by November or December that year, and so we were working, I don't know, we were crunching for six months, or something like that. We started in, like, May. By October, the end of September, early October, I remember the phone call with Mike saying, "You know, you guys are not going to make it, and we're going to delay this thing to next year." I couldn't accept it, I couldn't believe it, it didn't really register. It was like, "That's impossible, we're going to make it. We're going to do this, we're close." But, somebody who has a view from an outside perspective sees how far away you really are.

So, they said, "We're going to take a few extra months. Three months, four months, six months, whatever. We're going to try and do this, but you guys need to continue and kind of finish it up." So we ended up extending the crunch. I took off Christmas Day and I came back the next day, and things like that. It was really brutal.

Erich Schaefer

We were already going to go overtime. We knew we were taking too long. We were probably already over our estimated time, but nobody really cared, because the game was going really well. But I'm pretty sure it was '99, June, maybe even May, we said, "OK, we got to crunch to get this game done by the end of this year, by the end of '99." And so, we worked for four months, just really crunching too hard, and it took Blizzard South, it took this strike team to say, "You know what, you guys are not going to make it. This is not going to happen this year." That was super depressing, because we had been working so hard for four months, and we argued, but it took a day or two to sink in, that yeah, we're not going to make '99, we were crunching almost for nothing. Sure, we got a bunch of stuff done in this time, but, we're burned out and we're not going to make it, and that was a pretty depressing moment. We decided, OK, we're going to just work normally until the end of the year and get going again at the beginning of 2000. So that was my biggest moment of realizing, "Uh-oh, we're not even close. This is going to go a long time." It was a very depressing moment.

David Brevik

We were doing everything. "We got to do this, that, and the other thing. We have to get this fixed, and this has to happen." So, we were running around with our hair on fire for a year, and we were trying to- There was nothing that was one individual thing that we felt was going to hold us back. "Oh, this would have been complete if it weren't just for whatever. Oh, we were all sitting around just adding more content to the game, because we were all waiting on the Battle.net server to work," or something like that. There was nothing like that. Every part of it was behind schedule. Content was behind schedule. Monsters were behind schedule. Levels, story, cinematics, technology, it was all behind.

"We were already going to go overtime. We knew we were taking too long. We were probably already over our estimated time, but nobody really cared, because the game was going really well." - Erich Schaefer

The game was always playable. So, as we put in new levels and things like that, you could play it every day and iterate on it, start your character out and play stuff. So you could play up to the point where the content kind of stopped, and so it gave us the chance to go back and actually complete the content. It wasn't one thing in particular, it was that the content was only so far. Like, Hell didn't exist, I don't think, by the end of 1999. I think that we put that all in in 2000. So, that whole act, and that whole section there. I don't think that it started going in until February or March, or something like that, if I remember correctly.

Erich Schaefer

It was the assets, and it was the iteration on it to make it play well, and then the balance of all the skills, and of course, now we're in Act 3, and you have to do a whole other part of the skill tree, playing in the actual levels that it's going to be requires going back and revisiting the skill tree again. So every time we'd put something in, you kind of had to do this recursive look through everything you've made to that point and make the proper adjustments. It was grueling. We didn't have development tools like we do nowadays. Everything was a gruel. Getting assets into the game was done by hand by an engineer, and nothing was easy. Nothing came easy.

I remember I was making the interface for [the skills trees]. There was a stone slab, and the skills would all fit into these sockets. And I thought, "OK, we're basically done, I'll just make this skill tree and this stone slab, and then we will fill it out with skills". At least ten, twenty times, almost per character, I'd have to redo the stone slab with different positions for the skills and different hierarchies between them. And we never had a tool to do this, so I had to render out a whole new stone slab every time we changed a single thing. I made a ton of stone skill tree slabs art over and over and over that all just got thrown away. So, that was a great example, if we had better tools, or if we knew what the process was going to be, I wouldn't have put all that work into it.

David Brevik

I think people were loopy. We worked really hard and we worked late, and people played music, and they would go out and get a dinner and come back. Then sometimes we would do things like, "Oh, it's midnight. Farscape is on, so let's watch that for an hour," or something like that. It was 95 percent work, but there were little breaks here and there. There was a lot of office camaraderie around the late nights. Not everybody stayed late, but there was a good crew of, let's say ten people in particular that would stay late all the time. Some people would still stay late, don't get me wrong, stay until 9pm or 10pm, but that wasn't the 2am crew, or whatever. And then I'd get up at 6am and go to work and we'd do it all again.

Max Schaefer

We were always a couple months away, so if we just grind it out hard we'll be done with it. But it was mentally and physically exhausting. And people started to break down. People were getting sick all the time, they were breaking up with their girlfriends. It was bad. It was physically hard.

Erich Schaefer

It was physically hard. People would be sweating and you can just see the stress on their faces. We barely had relief. If someone had to take a week off or couldn't stay a few nights, other people would say, "Well, why aren't those people staying? We've got to stay." And we, as managers, as the people in charge, we didn't have good answers for that. We didn't handle it very well.

It wasn't all the worst times. Again, there was a lot of camaraderie, and there was good times to be had amongst this, but it's probably comparable to people on the front lines of a war. They get drunk and have a good time once in a while, but then it's back to the grind in the morning. What made it OK for me, and this is different for a lot of people, but I knew the game was going to be great. I knew we were on the right track. So, it was worth it. But that was not true for everybody. There were a lot of doubters who thought, well, I don't really like how it's going, either because they're stressed out or because they really didn't like it. So for those people, it would be even harder. I had total confidence, and that's what made it OK, that there was going to be an end and it's going to be great. But for people who didn't have that, it made it even worse.

For me, personally, a really weird experience is that I got married in May of 2000, which we thought was a very safe day to set the ceremony. And it turned out, it wasn't a safe date. We were working right through that time. And so, my poor wife had to handle all the arrangements and took on all the stress of the wedding. A lot of people picked up, my parents helped out a lot. But it was very odd that my wedding was coming up in the middle of this horrible crunch. So, at one point, I was just like, "OK, I'm leaving work, and I'm going to get my tuxedo, and the next day I'm getting married." I almost couldn't even think about the wedding. And then we kind of knew we were about done, so we were going to do a honeymoon at the end of June. And, we left on our honeymoon the week before we shipped. Now, all my stuff was really done, and it was just technical support things. But I just felt so weird. I've been here this whole time, and here at the very last days, I'm just taking off and leaving the crew behind.

Launch: Critics, Bugs, and the Stone of Jordan

Diablo II finally launched in the U.S. on June 29th, and in Europe on June 30th. The team wasn't finished yet, though. They still had an expansion to make, and there were bugs and hackers to deal with, too.

Erich Schaefer

I was in Paris when Diablo II released. And on the Champs-Elysees there was big banners, and the big Virgin megastore had a huge Diablo display. There were even TV commercials for Diablo in Paris. It all just felt so cool.

We knew immediately that it was selling really well. And then soon after, we learned it was selling really well in Korea. So, that was all great to hear, even though we were still fighting a lot of these technical issues. That would fall much more on Dave and the Battle.net team staff. Max and I were more on the creative end of things, and pretty much had washed our hands of the whole project. So it was easier for us than a lot of those guys, I'm sure.

David Brevik

The only thing I remember… there may have been some problems on launch day. We finally got those solved, and we brought everything back up, and got things running, and then there was this gold duping exploit, like, with splitting piles of gold. And I just remember it, day two, I felt like the whole thing that we had worked for, where we were doing this client server thing where everybody could be protected, and then we had blown our economy, or whatever, on like, Day 2. We were like, "Oh, my God, what did we do, we've blown it."

And so, it was just this emergency fix, getting those repaired and the exploit fixed, and stuff like that. Those are sort of the first memories I have of it. It goes straight into the frying pan of, you're in a live environment, and things are broken and you've got to fix them as fast as possible. Which was a new kind of concept for myself and the team, when you're doing these live products that are always on, that you have to respond to things in a much different way than you did with single player games, right? It's like, there's an exploit and we'll patch that at some point. We'll work on it over the next couple weeks, and maybe we'll put out a patch by the end of the month that fixes it. But if people want to destroy their game, I guess they can go ahead and do that. But most people won't.

That was kind of the mentality, and then there was even less of a mentality of that if there was a bug or an exploit like that on a cartridge game or on a physical CD console game, you know, they weren't fixed ever. So, now, things are put out and they're patched regularly, but that was very uncommon practice back then. It was really unusual. One of the things that really separated Blizzard from a lot of the pack was the fact that we continued to support and patch our products and get rid of bugs and problems and include enhanced features and stuff like that even after the game launched.

Erich Schaefer

Yeah, I think the first week was kind of a disaster, wasn't it? I was sort of luckily gone on this honeymoon.

Max Schaefer

Yeah, it was a disaster, but it was a good disaster, because it was over capacity, and that's why we were having the problems.

Erich Schaefer

I think by now, everyone has their cheating Diablo 2 story. They don't say it as if Diablo's a crap game because there's cheating, now they kind of talk about the fun and the weird experiences with the cheating. So, it doesn't bug me anymore.

David Brevik

At some point the Stone of Jordan became a kind of unit of currency. We we made a bunch of items, and sometimes when you're making items, you're making ones that are better than others, and [the Stone of Jordan] was deemed the most valuable item in the game. Even though it wasn't necessarily true, it was deemed as a rare item to find, as well as extremely valuable. So people started trading things for, and it would cost Stones of Jordan. But then people started duping Stones of Jordan, so Stones of Jordan were everywhere, and there were lots of them in the game, because there were lots of duping bugs and things like that.

"We finally got the [initial problems] solved, and we brought everything back up, and got things running, and then there was this gold duping exploit, like, with splitting piles of gold. And I just remember it, day two, I felt like the whole thing that we had worked for, where we were doing this client server thing where everybody could be protected, and then we had blown our economy, or whatever, on like, Day 2. We were like, "Oh, my God, what did we do, we've blown it." - David Brevik

Then we fixed the duping bugs, but there was still a lot of them out there. So we came up with a way to remove Stones of Jordan out of the economy, a sort of Stone of Jordan sink to get rid of them, so that they weren't all over the place any more. And that was this donation thing, where you could donate the Stone of Jordan and summon a Super Diablo or something like that. People today still, when they think of items in Diablo 2, it's the number one item that comes to mind, just because it was so valuable, and then used mainly as a currency for trading, and then just became the most popular duped item, and then there were just gobs of them in the economy.

Erich Schaefer

We were surprised when the SoJ became a unit of currency, but we were happy to see that dynamic occur. I always thought the gold cap was a bit too blunt an instrument, and it was neat to see players figure out this work-around.

David Brevik

It was a learning experience. It was the first time we had done client-server stuff, and so some of the mistakes that we made with the way that we were doing left too many holes, and items were being generated, and we figured out a way to generate unique IDs for them, but that wasn't necessarily in the code at the beginning. And, trying to improve on those systems to make duping more difficult and fixing all the flaws and the places you could cancel, and actually transferring the items instead of destroying them and recreating them.

When you're doing things like that, when you end up in a situation where one thing can get destroyed and another thing can get made, then the thing destroyed doesn't get destroyed because the player disconnected before that gets saved. There's all sorts of tricks that occur when you destroy the item and assume that it gets destroyed before you create the other version of it. So, it becomes a situation that's technically very challenging, but there's a lot that we learned there to make it more secure on future games that I worked on.

But again, I really feel like when people mention Diablo 2, the number one item that comes to mind is the Stone of Jordan. And, even though it became this big duped thing, it was a staple, it was the item to find, the item to seek. You were always happy to get one, and it became super-popular. So, in a lot of ways, it legitimized your account once you had them. And so I still feel like today that people still seek that item, even though maybe it's not the best item in the world.

Max Schaefer

We were so in the infancy of this type of game at that point that no one could have anticipated the level of effort people put into cheating. I mean, we kind of did because we went to client-server as a model, but it's so complicated to do what we were doing that there's all kinds of little vulnerabilities all over the place, and, for the most part, you could play and avoid cheating problems. And, when people did figure out some horrible way to cheat, eventually it would get fixed by the Battle.net team. And certainly, we've learned a lot from there that we apply these days to help cheating issues. But at the time, it just kind of came with the territory of making some of the first really giant global internet games where there's thousands of people trying to break it at any moment. That was a completely new and foreign thing, and the fact that it worked at all meant that we did a decent job of it.

Erich Schaefer

I do remember one story. I went to a GDC conference, after Diablo II, and one of the topics at one of the forums or whatever was, "Cheating in Games." And I said, "Oh, I should go check out cheating in games, because that's right up our alley right now." And then in the roundtable they were having, everybody just was trashing Diablo the whole time. They were saying, "Here's what Diablo does and why they were stupid, and here's all these things." And I was just getting really mad sitting there, just starting to think in my head. I didn't say anything there, I think I was just in the audience. But I was just thinking, Why don't you guys make a decent game first, and then work on cheating? Which is not fair, and I'm sure a lot of them did make decent games. But I do remember being really mad that everyone was focused on the cheating, when, in my mind, the game was so fun, who cares about the cheating?

David Brevik

A lot of people thought Diablo II was worse [than its predecessor], which wasn't very fun. But I think that in a lot of ways you can't really make games for the critics, you got to make the game that you want. You have to be satisfied with the effort that you put in and the job that you feel that you and your team did. It's like, in a lot of ways, I hate to say it, but it's a little bit like golf. You have to be happy with your golf score, not compare it to everybody else, or really making sure that you're pleasing everybody. Because you're not going to please everybody, and people are going to say stuff for whatever reason, and they may even change their mind. Yeah, they didn't like it at first, but now they really love it, because you made this one little change. And they were ranting and raving about 55 different things, but you make one little change, and they're like, "Oh, I love it now."

So, I think that you're going to get criticism no matter what you do. And this happens, not just in video games, but in any kind of entertainment, movies or music or books or whatever. I liked that one, or I didn't like this one, and everybody's entitled to their opinion, and opinions are free, so people are going to go ahead and say them. It's, how do you let it affect you. You need to focus on, how happy are you with the effort that you put in and the product that you made, and are you proud of what you've done, and are a majority of the people happy with what you created. I think that's the best way to look at it.

Max Schaefer

There was always people who didn't like Diablo, and that was true of Diablo 1 as well. Some people were absolutely convinced that we were killing the RPG genre by making it too arcadey, and that it wasn't even an RPG, and screw this game. But you could always tell that that was a distinct minority opinion, because people were playing it in droves, and buying it in droves.

Most of my time, I think, after release, in game, in the chat rooms, seeing what people were saying, and by and large those people were very excited, so, you could find the critics. And, we also were learning at this point that when you have a forum, a bulletin board service, on your website, that that tends to aggregate negative opinion. So you could kind of get a false impression of what people were thinking by looking in our forums versus actually going in-game and seeing what people were doing in game and how much fun people were having. But, like Erich, I think that we were so exhausted. We knew the game was good, and we almost didn't care what people were saying, because God, we just needed to get some sleep.

The Aftermath: Lords of Destruction, Patch 1.10, and Lessons Learned

Work began on an expansion pack for Diablo II almost as soon as it launched. It would be released the following year, and a steady stream of new features would contine into 2003 with Patch 1.1.

David Brevik

We almost always had planned on doing an expansion, and it started pretty rapidly, because the totally project length was maybe 14 months or something like that. So it was probably right around mid-summer that it really started in earnest, and we put people on it and we started making the new act and stuff. I think there were some ideas and concepts for it even right away, things that we want to fix. But the first focus was trying to fix some of the bugs and trying to stabilize the service and giving people a little bit of time off and a break, because people were burnt out. I was extremely burnt out. I think that that was really where the focus was for a few months after Diablo II.

Max Schaefer

We basically felt that we had left something on the table from Diablo 1 by not doing an expansion. We had farmed out an expansion for Diablo 1 that didn't turn out very good and wasn't a very good experience. So I think we had it in our heads that we weren't going to leave that opportunity on the table again, and that it would be relatively easy to do an expansion for Diablo II. So I don't recall there being any, "Hey, should we do this" or "shouldn't we do this." We knew we were going to roll off of Diablo II. And after we got caught up on sleep and repairing our familial relations, we knew that we were going to roll right into it.

One of the main goals we had in the expansion was to really plan it out so that it wouldn't go spiraling out of control, and really endeavor seriously to make a project on time and without this crazy crazy crunch at the end. So I think we kind of put the reins on being ambitious with expansion of the expansion as we went. We tried to stick to the script and hammer it out in a reasonable amount of time.

Erich Schaefer

Yeah, we learned some tough lessons on Diablo II that I think those guys really applied nicely to the expansion. I think almost everybody remembers Diablo really remembers the expansion and after the 1.1 patch. Honestly, that's how I remember it, too. I blur in my mind what was in each. But, we made some really great improvements, fixed up a lot of balance issues. I think it was just worth the continued effort we put into it that whole time to make it a great game. It was fun, and it sold well, but there was a lot of problems with the initial release, and that fixed a good many of them.

David Brevik

[Runewords] were just one of the features that we had been working on and that, because we had these socketed things, we could come up with letter arrangements. They were thinking of different types of items to socket into things. I don't know who came up with it, but the idea that we're going to make these words out of them, and different words turn the item into something else. I was not involved in those designs, so I don't exactly know where they came from.

I thought it was fascinating to have these, to not just know what you were socketing, but have this puzzle associated with the socketing game. I think that this hearkened back to other roguelikes where, in many roguelikes, the potions that you find or the scrolls or the items will all be unidentified, and you don't know what a potion is until you actually quaff it, and then you kind of find out. And then, once you've discovered what it is, it'll be labeled from then on. So, it was random each time, the purple potion in one game would be invisibility potion, but it would be poison in a different game. You didn't know what it was, and I loved that aspect of adventuring and trying to figure things out, and the mystery associated with those kind of things.

Capturing a little of that mysterious spirit in a game, especially in Diablo, was something that I always was looking for, but though we couldn't do it exactly the same way, I like the idea of experimentation and mystery around things, so the audience finds out how to craft and discover unique things about the game. So I love the idea of runewords, simply because that's the mystery that I think adds so much to the game, trial and error and discovering new stuff. It's so exciting to find recipes and whatnot, that's always something in gaming that I really enjoy, discovering the unknown. And you don't really have very many of those things as much anymore. Most people won't put them in the game, because they end up on the internet in ten seconds, so then it just becomes a hassle for people. People are upset that the interface isn't clear. It's kind of an era gone past, you know, games really don't do those kinds of things anymore, because they don't want to frustrate the players. The players want more instant gratification and ease of use than they did then. It was just a different time in gaming.

Max Schaefer

I think 1.10 added some longevity to the gameplay experience with the runewords and what have you, and the expansion pack really bumped the content level over the top. At that point, you had seven character classes that were fully fleshed out to play, you had a lot of really cool environments and a lot of dungeons and different kinds of monsters. It really kicked the amount of content over the top. And then, the other tweaks tightened the whole thing up. As a whole, it was a pretty good game.

David Brevik

It's funny because one of the things that people don't recall, and a lot of people today, especially younger people today, they don't even understand, is that the game was not super well-received when it came out, but when we put out the expansion a year later, that made a massive difference in people's opinions of the product. Because we were able to get a bunch of the bugs out, as well as improve and put in some critical new features that made the game much better, including a couple new character classes and a bunch of new items to get, polish the game better and put in new story... all of these really great features that added a lot to the product.

And then in 2003, the 1.10 patch changed a lot of things and put in synergies and all sorts of things. So I think that those kind of things, they see where it is, but they don't see the journey. They only see it now in hindsight as, "Hey, it was a classic, and it came out day one as this amazing thing." I think people still see that today, with, like, World of Warcraft. They go and play World of Warcraft, and they can't even imagine how different the game was when it came out versus now, right? How many things have changed, and how flying didn't even exist, and people were like, "What? I don't even understand what that means." Because they forget the journey that a project takes to get where it is, and they look at it with these rose-colored glasses, "Well, how is it today versus the way that it was when it came out?" They can evaluate it today, versus the way that it was.

And again, as you get further and further away from something you get these romantic notions about how wonderful something was, but then if you actually played it, you go back and go, "Oh, my God, I remember, I didn't like this, that, or the other thing." I think that still, there's more of a mythical whisper about how good it was versus maybe the reality.

It's a pretty big accomplishment to make such a well-revered game. People will still stop and talk to me often about how much they have playing the game, and they still have it, and they have fond memories. A lot of times now, it's like, "That was my favorite game when I was in fifth grade." I'm like, "Uh, uhat makes me old. "My dad and I played that when I was a little kid." I get that one too. So, it feels great to have been a part of that pretty magical experience. I feel super fortunate that I was able to do that and we're super lucky to be involved. A lot of times, success like that is all about timing and luck and all sorts of things, and, we were very very fortunate to be part of that. I'm super proud of what we created and super proud to be part of that team, something that most game developers will never experience.

Max Schaefer

It was pretty solid [after Diablo II] that this was going to be our career, that this is what we do, and that we couldn't continue to do it that way. It was going to kill us, it was going to burn everyone out, we were going to have massive turnover, we were going to hate our lives and what we did. I think we got away with it a little bit, but it was sort of a period where, whatever cool idea we had, we would cram into the game. And, there was not a whole lot of discipline as to trying to keep the bounds of the project within reason. I guess it had not come up before. There was not the opportunity to go spinning out of control like that.

"It's funny because one of the things that people don't recall, and a lot of people today, especially younger people today, they don't even understand, is that the game was not super well-received when it came out, but when we put out the expansion a year later, that made a massive difference in people's opinions of the product." - David Brevik

I think with Diablo 1, we were just so happy to be released from our budgetary constraints and to be working officially as a Blizzard company at that point. It was enough work to just get our original idea down and working that the project stayed pretty contained, and it wasn't really until Diablo II, where, we started to feel like, "Okay, we know we can make this sort of thing, now what kind of crazy things can we think of to do with it?" And that process just kind of spiraled out of control. And so, the big lesson was: Design within your scope, and within your budget, and within your size of your team, and don't just do every cool thing that comes up, because you're going to come up with a whole lot more cool things than you have time to implement.

It was such a wildly disproportionate success to anything that we could have expected or wanted, and then the whole way that we went from almost going out of business twenty times because didn't have any money and the milestone payments were late or whatever, going from there to having this giant franchise that you make... that people are still talking about today. It's just so inconceivable that you can't look upon it with anything but fondness at this point. Yeah, we screwed up and ground too hard for a while, and screwed up the schedules, and they were late, and there was little problems here and there with this and that, but overall, it's just all good, from my perspective.

Erich Schaefer

No regrets. It ruined a lot of lives, but it was worth it.

Thanks to David Craddock for providing the photos of Blizzard North. Concept art and sketches courtesy of Blizzard Entertainment.

_ddwYK80.png?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)