The Birth of Assassin's Creed, Sands of Time, and Legal Battles: Patrice Désilets Remembers a Decade With Ubisoft

"Once you receive [a mandate to redefine a genre], you can’t do a normal game again."

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

“Put 25 cents in the machine and I talk,” Patrice Désilets warns me. But I want him to talk. He’s excitable, cracks jokes and laughs a lot. He loves making games and it shows in the way he talks about them. Granted, his 21 year career has had its ups and downs. Extreme highs, like designing Assassin’s Creed, followed by extreme lows, like being sidelined from making games by legal dramas. And yet, the unpleasant experiences never dampened his enthusiasm for the art form he claims to still be discovering.

This sense of fun shows even in the office of Désilets' studio Panache Digital Games. For our interview, I’m led into a conference room through a door hidden in a bookcase. “When we opened the place we worked on it a bit,” Désilets' says. He tells me that he and the first few employees painted the walls themselves. They did a good job. “We level designed the studio, that’s why there’s a hidden door.”

The door serves a practical purpose, too. The potential hirees are led to their interview without seeing the whole studio, should they not be hired in the end. Ubisoft didn’t have such a thought out hiring procedure when Désilets applied for a job in 1997.

Rumor

It all started with a rumor Désilets’ mom heard while working for the government in Quebec City. The rumor had it that a big video company called Ubisoft was about to open a studio in Montreal.

Mind you, back in 1997 Ubisoft wasn’t yet the company we know today and the province of Quebec wasn’t the video game powerhouse that's employing more than 10 thousand people like it is now. Ubisoft saw the potential of the Québécoise, and Désilets, a filmmaking student on a break from school who worked odd movie set jobs like backup electrician and assistant editor, saw the potential of Ubisoft.

“The first email in my life was me sending my resume to Ubisoft,” he remembers. “I said I was a scriptwriter, which I was because I was writing a script,” he chuckles. But getting a job wouldn’t be that easy. Around two months later Désilets missed a call back from Alain Tascan, who was the producer tasked with setting up Ubisoft Montreal. “So I took the phone book and I called all the hotels in Montreal,” he says and admits he hates phone calls. The sacrifice paid off. “He was at the Sheraton, so at the end of the hotel list.” Désilets then wrote a letter saying “look I’m not crazy, I just wanna work for you,” and hand delivered it to the Sheraton. It worked and a couple phone calls later he secured a job interview.

Given the choice between interviewing for a position of a scriptwriter or a game designer, Désilets chose the latter. “I was 23 and cocky as hell, even more than now,” he says. There was only one issue. “I never did any games in my life.”

The preparation that consisted of reading back issues of Next Generation magazine paid off and got him two follow up interviews with one of Ubisoft’s founders Gerard Guillemot and with Sabine Hamelin the head of Montreal studio. Those went well too. “At the end Alain [Tascan] gave me a Playmobil toy of a little knight,” Désilets recalls. “And he said: ‘you’re starting in a week, think of a game.’”

Rhythm

Despite being a fan of LEGO and not Playmobil, he came up with the concept for a game called Hype: The Time Quest. The two and a half years it took to develop were the closest thing to education in game design Désilets would ever get. In the end, the game turned out to be a perfectly decent adventure title and an unforgettable career milestone. It earned Désilets a promotion to the position of the head of a separate design studio within the bigger structure of Ubisoft Montreal.

“I hired new game designers and most of them are still working in the games industry, which is something I’m really proud of,” he says. “During those months we learned what game design was.” Months, because his managerial stint ended rather quickly. “They realized, and it took me a bit longer to realize it, that I’m a much better game designer than manager."

He was then moved to lead a struggling production on Donald Duck: Goin’ Quackers, a fun platformer that taught him a few important lessons, from game design to corporate culture. “I learned a lot about rhythm,” he says. “How a character should have rhythm and then if the players can get better at the rhythm they enjoy it more.”

Working for a big corporation, he was about to learn, followed a certain distinct rhythm as well. “Welcome to a big corporation,” he chuckles. “I was asked—you’re just an employee, so you’re always asked and there's not a lot you can say—to work on Rainbow Six 3. I did the conception on it for six or seven months and then I was asked, 'it’s cool what you’re doing but you’re way better at third-person characters that jump, so you’ll do Rayman 4.”

A next installment in a high-profile franchise started by Ubisoft’s prodigy Michel Ancel sounded like a great career opportunity. It turned into everything but. When Désilets was ready to start work on Rayman 4, Michel Ancel decided the game wouldn’t be made in Montreal after all. Désilets was left with no projects to work on and absolutely nothing to do in the office for two months. “It wasn’t a fun time,” he says.

Towards the end of his involuntary hiatus, Désilets attended a presentation by the team working on the early conception for Ubisoft’s newest acquisition, Prince of Persia. He was intrigued, asked for a job on it, and got it right away. It turned out that the team had no designer on it. “It’s a bit stupid,” he says. “They could have thought of me, the guy who was doing nothing.”

Rewind

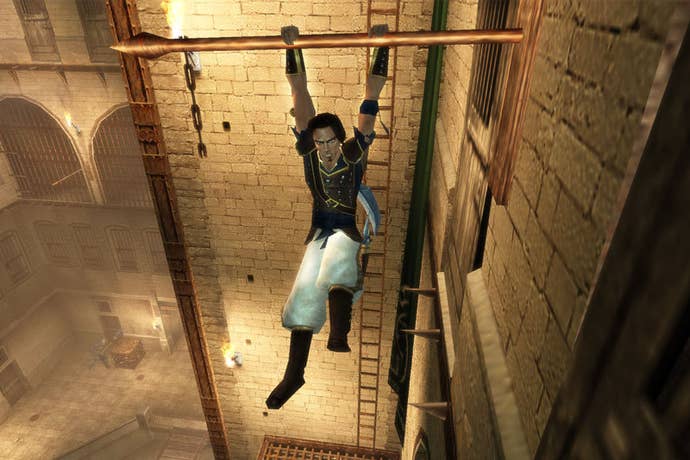

“We had good mechanics already, but we were dying a lot,” he says about his early work on Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time. “And respawn is a not a fun part of the game. [But] one morning in the shower, I just had this idea: why don’t we just do a rewind?”

He brought the idea up at the next team meeting. What if, Désilets asked, instead of a boring respawn they let the player rewind the game, VHS-style, to a moment just before they died? The question in the office wasn’t whether it was a good idea, but rather how to implement it. The solution came at a price. PlayStation 2 sported 32 megabytes of RAM and five of them were taken by the operating system. Désilets says that the rewind feature took between five to 10 megabytes. There wasn’t a lot of processing power to build a game with, and yet Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time showed few signs of technical constraints.

All in all, the rewind feature changed the trajectories of both Désilets and Ubisoft. “It was my very first realization that it’s neat to use what people are familiar with as a design feature. I call it organic design,” Désilets says. And all the limitations that the PS2 and the rewind feature imposed on the team would become the foundations for their next big hit.

Mandate

Upon his return from post-Sands of Time vacation in the January of 2004, Ubisoft laid out an ambitious task for Désilets: a mandate to "redefine the action adventure genre on the next generation of platforms."

Désilets had two issues with that directive. First, nobody at the time knew what the next generation of platforms meant, with the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 yet to be announced. Second, a mandate like that follows one throughout their career. “Once you receive it,” he says. “You can’t do a normal game again.”

To make things worse, the marketing department was disappointed with the early sales of The Sands of Time and had some words for Désilets too. The game eventually sold more than 14 million copies and proved massively influential, but its fantasy setting had been blamed for the initial underperformance. The new direction was to look for stories grounded in history and realism.

"Once you receive [a mandate to redefine a genre], you can’t do a normal game again."

Stuck on a puzzle, Désilets knew one thing about his next game. Despite it being what was then the new entry in the Prince of Persia series, he didn’t want a prince in it. “A prince is not an action character. A prince is somebody who waits for parents to die to take their place,” he says and backs it with the example of Charles, Prince of Wales. “He’s turning 70 this year and he’s still a prince, because mom is still around.”

Désilets went about things methodically. In his research he came upon the story of the secret society of Hashashins from Syria. “I thought, 'hmm, if you’re the number two assassin of that organization, that would make you a prince of Persia.'” Just like that Désilets killed two birds with one stone—he had a protagonist who was technically a prince and a realistic, historical setting.

The game was initially codenamed Prince of Persia: Assassins but two years into development it became its own thing: Assassin’s Creed. And the finished product defied the wishes of the marketing team that informed its conception. The Animus, the device for deciphering genetically transmitted memories that’s driving the plot of the series, was at odds with the call for realism but it opened the doors for sequels, thus making the business people happy. Animus was also a handy design feature for taking the dullness out of respawning, not unlike the rewind feature in The Sands of Time.

Village

The development of Assassin’s Creed was driven in big part by ideas Désilets wanted to put in The Sands of Time, but for technological or scheduling reasons couldn’t. For example, he wanted crowds. “Because of the PS2 we could only draw six to eight characters at the same time. Six characters is not a crowd, it’s just a group,” says Désilets. The newer consoles, PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360, presented no such limitations and hiding in the crowd became one of Assassin’s Creed's essential mechanics. And then there was another unrealized ambition.

Désilets remembers the village at the bottom of the palace in The Sands of Time the team had to cut due to time constraints. “This time I wanted to play the village. I wanted to jump from rooftop to rooftop,” he says. But it was about much more than just the freedom of choosing the rooftops to jump on. “Everybody played The Sands of Time the way I played. You can not be much better at it. You can be faster, but not really better.” An open city with many ways to reach the same goal provided plenty of room for setting the best players apart. And it didn’t hurt that the cities in the game—Jerusalem, Damascus and Acre—were a perfect blend of historical accuracy and fun design. That particular balance, surprisingly, wasn't actually that hard to hit.

“We didn’t have to do a lot of compromises because [the cities'] architecture is already in a way made for climbing,” he says and backs it up with examples of real-life parkourers and skyscraper-climbing daredevils. “I had a chance to go to Jerusalem 10 years after I finished the game and I was like, ‘oh s**t, we did a good job.’ Because we didn’t go before, we just looked at the pictures.”

There were a lot of pictures to look at. The team’s goal was to be as accurate and thorough in their research as possible. But to make sure the historical background wasn’t too convoluted, they followed a simple 30 second Wikipedia rule. “If it takes less than 30 seconds to find it on Wikipedia, then it should be the truth,” Désilets explains. "If it takes you three weeks in the old books in Oxford, then who cares?”

For his part, Désilets also discovered new things about working on such a high-profile project. Not all of them pleasant. “We had a good time but it was a tough time all the same. There were many unknowns: technology, game design, marketing, building this IP and the team going to from 60 on The Sands of Time to 200 on Assassin’s Creed,” he says. “That was a bit tough. Some of the people were afraid to talk to me because they only talked to me once every six months. And then on Assassin’s Creed 2 it became 800 with people outside of the studio working on it.”

Complaints

“We knew how all the complaints would be,” Désilets says about the Assassin’s Creed’s reception. “There were a lot of subquests in AC that were designed and ready to be built, but it took months to do one side quest because we didn’t have the tools yet.” The difficult decision decision had to be made late in the development process: the game would ship with just the main storyline that followed assassinations of nine bosses. “It was really pure, but for some people it was lacking variety,” he admits.

By the time the work on Assassin’s Creed 2 started, the team was ready in every respect. They knew each other, they tamed the technology and they understood the IP they just created. All of that showed in the finished product. Assassin’s Creed 2 gained universal acclaim and fixed most of its predecessor’s flaws. Those fixes however, according to Désilets, weren’t a result of purposely addressing the criticisms, but of simply casting a younger protagonist.

“Our main issue with Assassin’s Creed was Altair [the game’s protagonist] already being a master assassin, and the game roughly is about teaching the player how to play the game,” he says. “As soon as Ezio [the protagonist in the sequel] comes in, Ezio and player are the same. They're both young assassins. And since the game and the story are about Ezio becoming this master assassin, the game design and the structure fit with the narrative.” In other words, Ezio became the perfect exemplification of Désilets' principle of invisible game design. Ezio’s vendetta served as a perfect device for teaching the players how to be assassins without snapping them out of the experience.

And Désilets says that the story of a young assassin’s rise to the top could have been told in any historical setting, as long as it wasn’t a repeat of the Holy Land. “We needed the second one to be elsewhere to establish that the series is not about the crusades.” From a list of about 20 potential epochs in places like Russia, Japan and Egypt, the team settled on the Italian Renaissance. “Italy,” he says. “I lived there for a year and we had a lot of people on the team who liked Italy. Plus we were in 2008, still in The Da Vinci Code moment. It all fit together,” he explains.

Assassin’s Creed 2 outsold and outclassed the first game, and to this day remains the best reviewed installment of the series.

Plague

“First, I took a year off. That was very important. I needed it,” Désilets says about his departure from Ubisoft in 2010 after he got burned out and disillusioned by the realities of creating a bestselling franchise.

Upon his return from a long vacation, Désilets signed on with the newly formed THQ Montreal and started work on his next game, 1666: Amsterdam. Not long after that THQ went bankrupt and Ubisoft—oh, sweet irony—picked up THQ Montreal’s assets, among which were Désilets' contract and the rights to the game he was working on. “Suddenly the people from Ubisoft I left a couple of years ago were back in my office,” he says. Désilets was once again employed by Ubisoft and in an atmosphere of reconciliation went back to work on his passion project. But it wasn’t meant to last.

"We got fired and got kicked out on the street. I had to ask for my bag, keys and wallet. [...] That's something I will never do to my employees."

A couple of months later, after what can be gathered was a period of infighting, Désilets’ and Ubisoft’s differences proved unsolvable and he was fired from the company. But he wasn’t done fighting with Ubisoft just yet: he now wanted 1666: Amsterdam back. Three years of legal battle ensued and eventually the two parties settled out of court. “I basically spent all the money I had put aside to make sure I got the game back,” he says. It was worth it though. The rights to 1666: Amsterdam are now in the rightful hands of Désilets, who promises to make the game eventually.

“It was tough because I’m just making games. That’s all I want to do, but I want to do it my way,” Désilets opens up. “For three years of my last ten I was put aside. Once because I wanted it, and two years not because I wanted it. I couldn’t work because of the non-compete clauses after leaving Ubisoft, and then I had no place to work. For a year I was untouchable. I had the plague."

For what it's worth, Désilets wasn’t alone in those hard times. By his side was his long-time friend and future co-founder of Panache Jean-François Boivin. “He also got pushed aside when he was at THQ with me. He got fired that same day,” Désilets remembers about their departure from the crumbling THQ after acquisition. “We got fired and got kicked out on the street. I had to ask for my bag, keys and wallet. When you get fired you don’t think about stealing data. That’s not how it works. You think about your family, about losing your house.”

“That’s something I will never do to my employees,” he says.

After all the legal dust around Désilets’ firing from Ubisoft settled, the duo was ready for their next challenge. They got invited to pitch to some potential investors. Almost on the spot, Désilets and Boivin came up with a bunch of game ideas and a company called Panache Digital Games to go along with them.

While their particular pitch didn’t work, Désilets and Boivin now found themselves with their own game studio. “A year after our non-compete clauses were over, we incorporated Panache Digital Games,” he says. What followed was another break from making games. “For the second year we didn’t work. We pitched and we pitched.”

His idea for Panache’s first game was something small and simple, a warm up for the team and the technology it would have to build. "But then when I pitched it people said: ‘yeah, but where is Assassin’s Creed?’"

Evolution

“I’m stuck. People want a historical game out of me,” Désilets says. “But I cannot make Jerusalem or Florence with a small team right from the start.” And then, a revelation came to him. “If I do prehistorical game, I don’t have to build a civilization. I can focus on a character and a 3D world because that’s all there is to it.”

With the theme of human evolution serving as a tool for game progression, all the pieces of the puzzle for Ancestors: The Humankind Odyssey fell in place. Ancestors started out as an episodic game, but with an injection of cash from a publisher blossomed into an an open world,single player action-adventure survival title.

Now with the backing of Take-Two’s indie label Private Division, the studio has grown as more and more people—many of whom worked with Désilets before—make it through the bookcase. “When the studio opened there were six of us,” he says. “And now we’re 32, some may say 33 with accounting.”

They won't share a release date yet, but the team treats the game as if it was out already, which means multiple fully playable builds a day. It’s Friday and they’re about to cap the week off with an afternoon session of the lastest of them. I need to leave before then. As our time is coming to an end, I ask Désilets what the common thread is between all of his games. I don’t expect the answer to be this simple and profound.

“It’s a little character that jumps around.”

_ddwYK80.png?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)